The tension between religious exclusivism and divine universality has long marked the spiritual journey of humankind. One recent conversation captured this dynamic with striking clarity. “Judaism is not a universalist religion,” a Jewish client remarked. “We are exclusivist.” In that singular statement lies an entire theology of election, suffering, memory, and resistance. But the question it provokes is even more unsettling: Has exclusivism become a spiritual idol? When covenantal identity is preserved at the cost of openness to God’s redemptive work in Christ, is it truly still faithfulness, or is it fear?

Judaism understands itself not as a missionary religion, but a covenantal one. Its calling, rooted in the election of Abraham and the giving of the Torah at Sinai, is not to make converts but to live distinctly before God. And yet the Scriptures themselves caution against misreading election as superiority: “It is not because of your righteousness or the uprightness of your heart that you are going in to possess their land…” (Deuteronomy 9:5).¹ The covenant, then, is not a reward for moral excellence but an assignment rooted in divine purpose and the failings of surrounding nations.

Even the origin of that covenant defies exclusivist pride. Abraham who becomes the progenitor of the Jewish people was not Jewish. He was a wandering Aramean, a pagan from Mesopotamia, chosen not for his purity but for his willingness to respond to divine invitation. His calling was not inward-looking. Rather, God said to him, “Through you all the families of the earth will be blessed” (Genesis 12:3).² Election, from the beginning, was missional, not tribal.

But how has a theology of vocation become, in some cases, a theology of insulation?

Modern Jewish identity has been shaped profoundly by trauma. The loss of Temple, the scattering through exile, centuries of marginalisation, and most catastrophically, the Holocaust, have formed a people whose collective memory is infused with pain. The frequent phrase “We will not forget” does more than preserve dignity; it often becomes identity. But when suffering becomes sacred in and of itself, it can lead to what Marc Ellis terms a “cult of innocence,” where victimhood shields a people from self-examination.³ Theologically, this becomes a kind of victim-based exceptionalism: We have suffered most, therefore our moral position is unassailable.

Edward Said, writing from a Palestinian perspective, warned that when memory is employed as a shield against ethical responsibility, it ceases to be liberative and becomes exclusionary.⁴ This is not to dismiss Jewish suffering, far from it, but to ask whether memory is being sanctified as a moral licence. If identity is shaped chiefly by pain rather than promise, then even the covenant can be weaponised.

This leads us to a difficult, but necessary question: Why do Jews reject Jesus, their own historical and ethnic brother, despite the deep theological and historical evidence for his messianic identity?

The reasons are multiple. Historically, Jesus failed to meet the popular expectations of the Messiah. He did not deliver Israel from Rome; he was executed by it. He did not restore the kingdom to David; he spoke of a kingdom not of this world. More profoundly, he claimed divine identity: he forgave sins, received worship, and reinterpreted the Law. For most Jewish authorities, this was unacceptable. God is echad, One, indivisible (Deuteronomy 6:4.)⁵ Incarnation and Trinity violate the very core of Jewish perspectives of monotheism.

Then came empire. Christianity, once a Jewish sect, became Roman, Latinised, imperial. Sabbath became Sunday, Torah became irrelevant, and Jews, shockingly, became scapegoats. By the fourth century, to become a Christian often meant to reject Jewish customs and theology altogether. In this context, Jewish rejection of Jesus is not mere stubbornness, it is self-preservation. As Amy-Jill Levine argues, Jewish non-acceptance of Jesus must be read not only theologically but historically and politically.⁶

Still, not all Jews have rejected Jesus. Messianic Jews, those who believe in Jesus (Yeshua) as Messiah and retain Jewish identity and practice, represent a theological middle ground. Often marginalised by both rabbinic Jews and Gentile Christians, they insist that Jesus did not abolish Torah but fulfilled it. Mark Kinzer contends that the promises to Israel are “transformed in Messiah, not terminated.”⁷ But such claims remain contested within broader Judaism, which continues to see Messianic movements as Christian infiltration, not Jewish continuity.

For Christians, this leads to another problem: the danger of supersessionism, the belief that the Church has replaced Israel as the true people of God. Paul anticipates this in Romans 11, warning Gentiles not to become arrogant: “Do not be arrogant toward the branches… remember it is not you who support the root, but the root that supports you” (Romans 11:18).⁸ The Christian claim is not that the covenant is void, but that it is fulfilled in Christ. As N.T. Wright notes, “Jesus is the place where Israel’s vocation is completed and extended to the world.”⁹

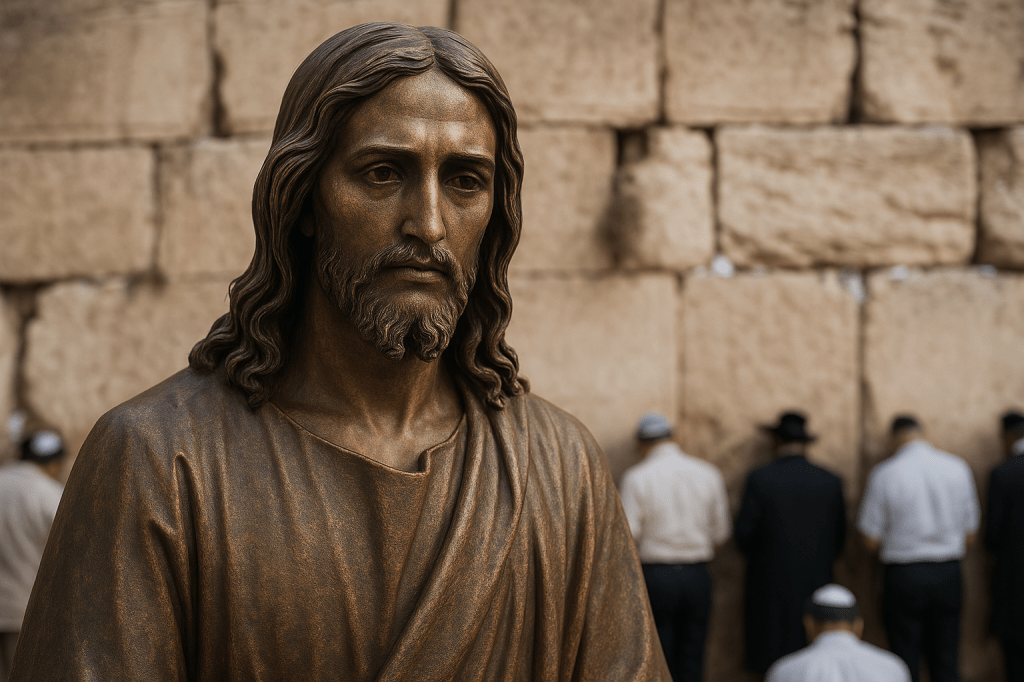

And this, finally, brings us to Jesus himself. Beyond Jewish failure, Christian distortion, and historical trauma, Jesus stands alone. He kept the covenant no one else could. He fulfilled Torah, embodied Israel’s vocation, bore the curse of the Law, and rose again beyond time, culture, and race. Paul declares, “In Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek…” (Galatians 3:28).¹⁰ In Him, identity is not erased but redeemed. Supremacy, whether ethnic, religious, or moral, is crucified.

So we return to the beginning. Is it possible that in clinging to covenantal identity outside of Jesus, some Jewish theology has inadvertently placed identity above God? When memory becomes untouchable, when chosenness is romanticised, when Messiah is rejected to preserve historical pain, then perhaps even sacred identity must be brought to the cross.

Jesus, the Jewish Messiah, does not erase the covenant. He magnifies it. But only for those willing to let go of supremacy in all its forms and be born again, not into a new religion, but into a new creation.

If identity, however sacred, stands between us and Christ, are we still bearing witness to God, or only to ourselves?

References

1. Holy Bible. English Standard Version. Wheaton: Crossway, 2001.

2. Holy Bible. English Standard Version. Wheaton: Crossway, 2001.

3. Ellis, Marc H. Beyond Innocence and Redemption: Confronting the Holocaust and Israeli Power. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1990.

4. Said, Edward W. The Question of Palestine. New York: Vintage, 1992.

5. Holy Bible. English Standard Version. Wheaton: Crossway, 2001.

6. Levine, Amy-Jill. The Misunderstood Jew: The Church and the Scandal of the Jewish Jesus. New York: HarperOne, 2006.

7. Kinzer, Mark S. Postmissionary Messianic Judaism: Redefining Christian Engagement with the Jewish People. Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2005.

8. Holy Bible. English Standard Version. Wheaton: Crossway, 2001.

9. Wright, N.T. Paul and the Faithfulness of God. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2013.

10. Holy Bible. English Standard Version. Wheaton: Crossway, 2001.