Post-Traumatic Growth and the Third Day of Pain

Personal Reflection

When I first began therapy, twenty-six years ago, I kept hearing a statement that drove me absolutely mad: “You must sit with your feelings. Don’t edit them. Don’t dismiss them. You must feel them in order for the healing to come.”

I loathed it.

Not because I didn’t have feelings, but because I had mastered the art of pretending I was fine. Years of physical abuse had taught me that pain must be hidden to avoid more pain. Later, in adulthood, drugs became the tool to numb it. So when therapists invited me to feel, truly feel, it was a double-edged sword. I had to face the horror of what I had survived and learn that I was finally allowed to have feelings.

I had grown up with the phrase: “If you cry, I’ll give you something to cry about.”Emotion was a liability. Weakness. So when I finally began to feel again, there was a strange grief that came with it. I was mourning a version of myself I had built for survival, while realising I no longer wanted to be him.

But in that process, I encountered Jesus. And I discovered something sacred: my darkest feelings were never too dark for Him. He walked me through my fury at the world, my numbness, my shame, my mourning, and my fear. And through the power of the Holy Spirit, I began to love God, not as a theological idea, but as the one who stayed with me in the pit.

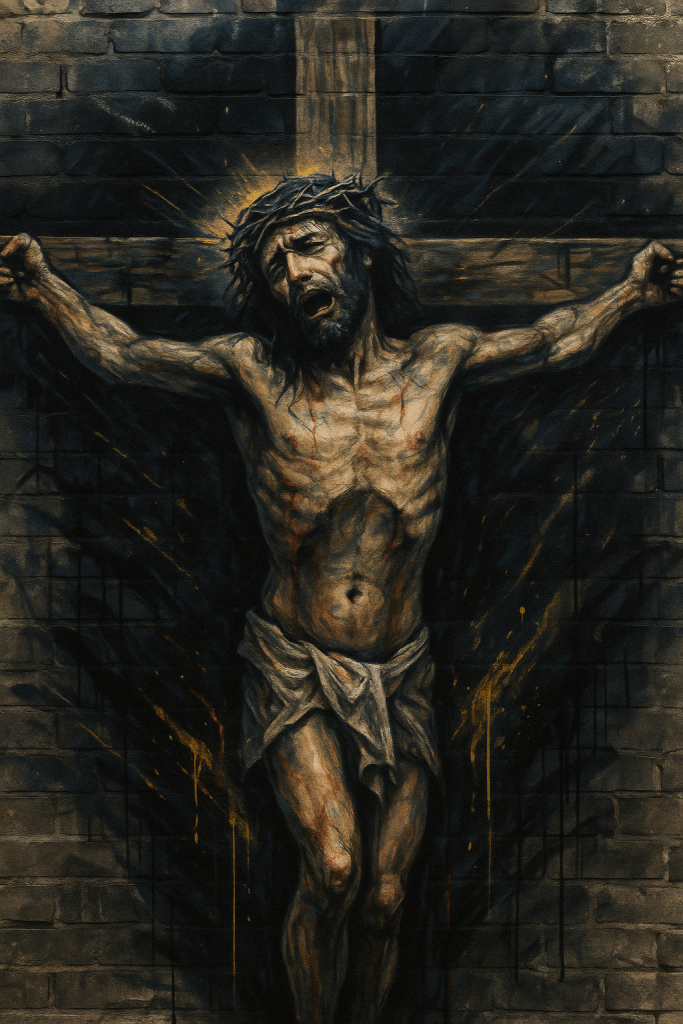

I cannot imagine what it is like to be crucified. But I know this: a crucifixion saved me, from the man I was becoming. From the pain I couldn’t name. From the death I was heading toward. His suffering made room for mine, and His death made possible my new life.

Stage Three: Grief and Despair

In the psychology of post-traumatic growth, stage three is grief and despair. This is the emotional freefall after the initial shock. It is the part of the trauma journey where nothing makes sense and hope feels absent. Psychologists Elizabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler describe it not as a step to rush through, but as a transformative descent.¹ “You will not ‘get over’ grief… you will be changed by it.”

Trauma researcher Judith Herman refers to this phase as “traumatic bereavement,” the compounded sorrow of both what was lost and how it was lost.² Despair, in this sense, is not just emotional, it is spiritual. It can feel like abandonment by meaning itself.

Paul Tillich calls this the “existential form of the state of sin,” not in the moral sense, but in the experience of disconnection from God, truth, and self.³ Despair, he writes, is the awareness that “the ground beneath us has cracked.”

And yet, as Henri Nouwen reminds us, the place where we feel most rejected is often the place where healing begins. “The greatest pain comes from feeling rejected by God,” he writes, “but that is also where healing begins.”⁴

Good Friday and the Silence of God

The Gospels tell us that from noon until three, darkness covered the land (Matt. 27:45). Jesus then cried out, “My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?” (Matt. 27:46). This is not a rhetorical cry. It is the human scream of divine silence. Rowan Williams insists that “the silence of God is not His absence, but the depth of His solidarity.”⁵

Jesus is quoting Psalm 22, a lament. He is not performing. He is feeling. In that moment, Christ identifies fully with the forsaken.

And yet, as Serene Jones argues, grace is often found “in the ruptured spaces” where theology fails and agony begins.⁶ Trauma breaks our narratives; grace begins by meeting us in the fragments. Shelly Rambo expands this: “Resurrection is too quickly proclaimed. The Spirit teaches us how to remain.”⁷ The theology of despair insists we do not skip from cross to empty tomb. We remain. We weep. We wait.

The followers of Jesus were not only mourning His death, they were watching their kingdom dreams dissolve. As they would later confess, “We had hoped that He was the one to redeem Israel” (Luke 24:21). Their Messiah was gone. Their hope had died. Gustavo Gutiérrez calls this God’s solidarity with the suffering: “God does not love suffering, but loves the person in pain.”⁸ Even in death, Jesus was standing with the broken.

The Lament that Refuses to Be Comforted

For trauma survivors, grief is often entangled with identity loss. As I once mourned the person I used to be, I came to understand what Emmanuel Katongole calls born from lament, faith that grows not in clarity, but in crying. “To lament is to refuse to be comforted by anything but God.”⁹

Nicholas Wolterstorff reflects on his own mourning after the loss of his son: “We carry the wounds not as burdens, but as sacred reminders.”¹⁰ Grief, when embraced, can become consecrated ground.

Even the Roman centurion at the cross sensed something had shifted: “Surely He was the Son of God!” (Matt. 27:54). Creation mourned. The veil tore. The sky darkened. The earth shook. The world itself lamented.

And in that grief, a slow movement began, not yet a resurrection, but a space cleared for it.

Practical Application: Remaining in the Middle

So what does this mean for us?

It means we do not rush people through pain. It means we learn to sit with our feelings and our friends’ grief without trying to fix it. It means we understand the value of spiritual lament, not as lack of faith, but as the fullest expression of it.

As John Swinton reminds us, “To lament is not to give up on God, but to wrestle with Him in love.”¹¹ In trauma care, in discipleship, and in our own suffering, we must learn to stay in the Friday spaces. Let Holy Saturday take as long as it takes. The resurrection will come, but the wounds will remain as testimony.

A Prayer in the Darkness

Father God, Jesus, Holy Spirit,

You did not skip past suffering.

You entered it, fully, painfully, redemptively.

Help me to do the same.

Help me not to numb my grief, nor to rush my healing.

Teach me to remain, like Mary at the cross.

To cry, to wait, to remember.

Thank You for being present even when silent.

Thank You for understanding my despair.

Thank You for holding me, not only in victory, but in the valley.

I grieve what I have lost.

But I trust that in Your hands, grief becomes holy.

And wounds become testimonies. God,

You are the Light who did not flinch at the dark

In Your Holy Name King Jesus,

Amen.

Footnotes

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler, On Grief and Grieving: Finding the Meaning of Grief Through the Five Stages of Loss (New York: Scribner, 2005), 76.

- Judith Herman, Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror(New York: Basic Books, 1992), 62–63.

- Paul Tillich, The Courage to Be (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1952), 46.

- Henri Nouwen, The Inner Voice of Love: A Journey Through Anguish to Freedom (New York: Doubleday, 1996), 23.

- Rowan Williams, The Wound of Knowledge: Christian Spirituality from the New Testament to Saint John of the Cross (London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1979), 88.

- Serene Jones, Trauma and Grace: Theology in a Ruptured World(Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 47.

- Shelly Rambo, Spirit and Trauma: A Theology of Remaining (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 128.

- Gustavo Gutiérrez, A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1988), 236.

- Emmanuel Katongole, Born from Lament: The Theology and Politics of Hope in Africa (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2017), 94.

- Nicholas Wolterstorff, Lament for a Son(Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987), 34.

- John Swinton, Raging with Compassion: Pastoral Responses to the Problem of Evil (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 101.