What John 11 teaches us about death, identity, and the distortion of truth.

Introduction

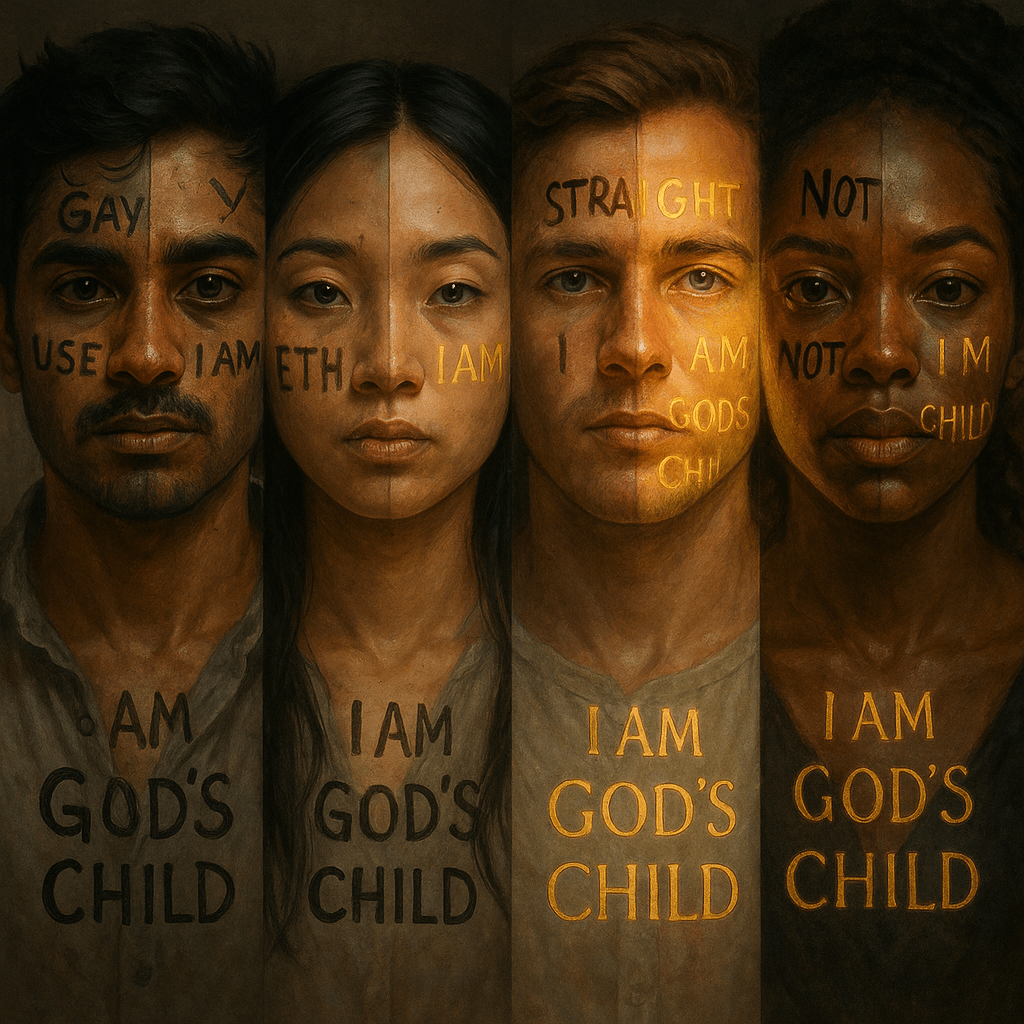

“I am not who I thought I was. Neither are you.”

So begins the slow unraveling of our illusions. The life we inherit is more theatre than truth, a script crafted by repetition, trauma, and cultural catechism. I was fifty-one years old when I finally began to see through the haze. In my twenties, I had been so desperately busy trying to be everyone else, that I hadn’t realised how deeply I’d lost myself. Or rather, I had never truly known who I was to begin with.

This is not just autobiography. It is the confession of a generation. We are all shaped, contorted even, by what might be called quasi-perceptual dysphoria: the internalization of unverified truths that masquerade as self-knowledge. It’s the anorexic who sees fat where bones protrude. The traumatised child who believes they caused their parents’ divorce. The soul that confuses affirmation with identity.

And yes, it is the entire global conversation around identity that finds itself entrenched in a new epistemic crisis: not just what we are, but how we know who we are.

Quasi‑Perceptual Dysphoria: Naming the Problem

In psychology, quasi-perceptual beliefs are convictions formed not through external verification but internal distortion. The mind feels truth, even when the facts refute it. In a world where internal perception is rapidly becoming the highest moral authority, this poses a serious problem.

Modern identity theory proclaims, “If you feel it, it’s real.” Yet Scripture, neuroscience, and cognitive psychology all whisper otherwise.

“This sickness is not unto death, but for the glory of God…” (John 11:4)

Jesus’s words to His disciples regarding Lazarus’s illness were startling. He redefines death not as biological cessation, but as something much deeper. His delay in visiting Lazarus was not indifference, it was divine intent. He was about to dismantle their perception of death and replace it with revelation.

Likewise, the identity crisis of our time is not merely about biology or behaviour. It is about epistemology, how we know what is real, and how easily that process is corrupted.

The Science of Repetition: Truth by Illusion

Modern neuroscience has verified a disturbing trend: we believe things not because they are true, but because we’ve heard them often enough. This is called the illusory truth effect, the tendency to accept falsehoods as true through repetition.

In a landmark study, researchers found that familiarity, even without evidence, increased perceived truthfulness, even when participants knew better originally.¹

This has powerful implications for identity formation. Slogans like “Love is love,” “Trans women are women,” or “Born this way” become moral absolutes not because they are examined, but because they are repeated. Social media algorithms, echo chambers, and political scripting amplify this effect. Truth becomes a product of frequency, not substance.

As philosopher Lee Braver reminds us, “Instead of blithely assuming we are directly gathering information from the object of our examination, we must turn our gaze around to critically examine the tool by which we are conducting our examination.”²

In other words, we must interrogate not just what we believe, but why we believe it. This includes our sense of self.

Entropy and Divine Realism

Science teaches us the law of entropy: that all systems tend toward disorder. It explains why everything ages, decays, and dies. But this isn’t just physics, it’s theology. Scripture affirms this universal decline, not as a random defect, but as a symptom of spiritual separation from God.

In Romans 8, Paul writes that “the creation was subjected to frustration… in hope that it will be liberated from its bondage to decay.” This is not the language of nihilism, but of redemption. Entropy points to a deeper need: resurrection.

Our cultural obsession with self-definition is, in part, a reaction against this decay. If the body is breaking, redefine it. If biology limits, override it. But such efforts only highlight our fundamental estrangement from reality. As neuroscience confirms, even our brain’s perception of self can be disrupted by trauma, neurochemical imbalance, or cultural contagion.

Truth, then, cannot begin within the self, it must descend from beyond it. And this is what Jesus does.

Jesus’ Redefinition of Death

When Jesus says, “This sickness is not unto death,” He isn’t being evasive. He’s exposing the disciples’ limited ontology. What they call death is merely a sleep. What they call life is often illusion.

Later in the chapter, He weeps, not because Lazarus is gone forever, but because His own are trapped in a perceptual dysphoria. They mourn what God intends to resurrect.

Jesus doesn’t just raise Lazarus. He rewrites what life means. He proves that death, as we define it, is insufficient to capture the fullness of divine reality. “I am the resurrection and the life,” He declares. In doing so, He reorients all definitions of identity, purpose, and destiny around Himself.

Escaping Dysphoria: Surrender and Resurrection

Quasi-perceptual dysphoria is not merely a psychological error, it is a spiritual malnourishment. It is what happens when we substitute perception for revelation, and when slogans replace Scripture.

To be delivered from this dysphoria is not to reject all feeling, but to surrender it to truth. The path to healing is the path to the tomb, where Lazarus lay: complete surrender, followed by divine speech. “Lazarus, come forth.”

That’s how identity is formed, not by willpower, or popular consensus, or even trauma recovery, but by the voice of the One who formed us in our mother’s womb.

Final Call: Come Alive Again

Identity isn’t self-made. It’s God-spoken. And death, as Jesus shows, is not a final verdict but a temporary veil, one that must be pulled back to reveal the glory of God.

You are not who you thought you were. You are far more. Not because of what you feel, but because of what He says.

“I have come that they may have life, and have it more abundantly.” (John 10:10)

This is not theory. This is resurrection.

Practical Application: Realigning Perception with Revelation

Pause your assumptions. Ask yourself: Is what I believe about myself or others rooted in truth, or repetition, emotion, or culture?

Invite Scripture to define reality. Start with John 11. Let Jesus’ understanding of death reshape your understanding of life.

Surrender perceptions that clash with God’s Word. Don’t shame them. Lay them down. Say aloud: “Jesus, I choose Your truth over my own interpretation.”

Speak life. Memorise or declare John 11:25–26.: “I am the resurrection and the life. Whoever believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live, and everyone who lives and believes in me shall never die.” Let God’s truth enter your neural pathways, not just as belief, but as identity.

Live in anticipation of resurrection. Not just at the end of your life, but in every broken or confusing place today. What you call dead, He may be preparing to call forth.

A Simple Prayer

Jesus,

I have often mistaken perception for truth. I confess that I’ve let culture, pain, and pride define what only You can reveal.

Speak into my confusion. Raise me from my dysphoria. Replace my false self with the identity You authored before time began.

I choose life, not the illusion of it, but the fullness found only in You.

In Your Holy and Mighty name Lord Jesus,

Amen.

Footnotes

[1]: Hasher, L., Goldstein, D., & Toppino, T. (1977). Frequency and the conference of referential validity. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 16(1), 107–112.

[2]: Braver, Lee. A Thing of This World: A History of Continental Anti-Realism. Northwestern University Press, 2007.