Introduction

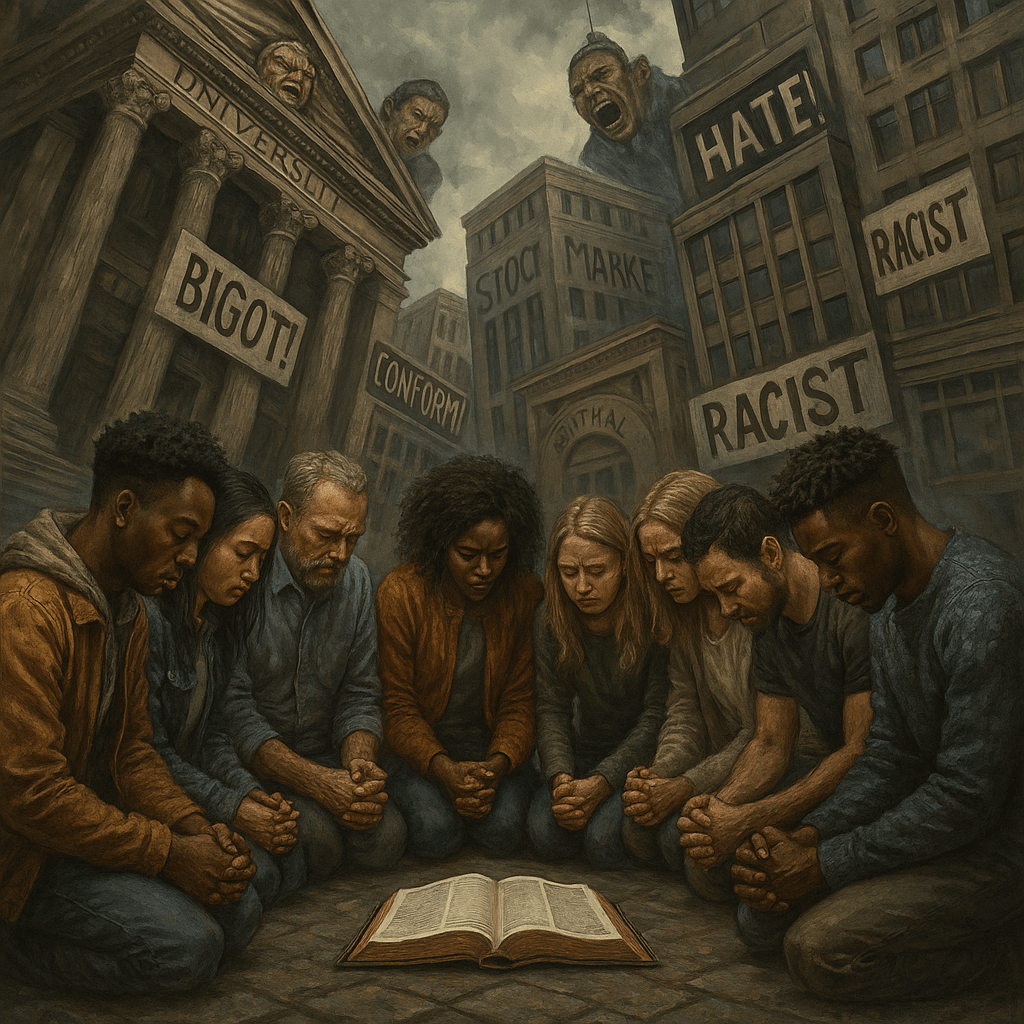

I have spent most of my life trying to figure out whether I think who I am is who I am, or if it is who the world told me I was. I’ve been called “faggot” “white coloniser” “#menaretrash” “white privileged” “wrong side of the tracks” “dumb hairdresser” “bigot” “homophobic” and every insult under the sun one can think of. I may be white privileged in so far as my skin colour was favourable during apartheid in South Africa. However, I was expected to fight for my country on the automatic assumption of being white, despite me not believing in my country’s politics.

I refused.

The point is that I, like all of us, have been subject to the labels of Identity Cards, social categories, positional worth, and academic Dewey systems. Who we think we are is influenced by what the world has imprinted into us. My encounter with the God of the Holy Bible as a true living entity has allowed me to choose to learn to be defined by who God says I am. It is not easy because this makes me an enemy of the world who consistently bullies me to conform into its agenda to “fit in.”

I once thought that my sexual identity was my authentic self, and then I learned that even that was socially constructed by social contagion. And so my walk with Jesus became the profound life-line I never knew I needed if I was, and am to learn who I really am supposed to be. So far, I love being who Jesus says I am: beloved, chosen, royal priesthood, lovingly created with detail.

Then…John 10.

“And Jesus Walked…” (John 10:22–23)

“Now it was the Feast of Dedication in Jerusalem, and it was winter. And Jesus walked in the temple, in Solomon’s porch.” — John 10:22–23

It is not accidental that John includes this detail: Jesus was walking in Solomon’s porch during the Feast of Dedication (what we now know as Hanukkah). Jesus, who says He does nothing unless He sees the Father doing it (John 5:19), was doing something. He was walking where Israel’s rulers had long imposed their systems of control, the courts of religion, reason, and reputation.

Solomon’s porch, once thought to connect the temple to its past glory, had become a space where social pressure, philosophical systems, and institutional identity converged. This is where the religious leaders cornered Jesus with loaded questions. And here, Jesus was not preaching, healing, or performing miracles. He was walking.

Deliberate.

Present.

Watching.

He walked right into the field of emotional and social manipulation. He walked among the “they,” the institutional powers and social engineers, not to conform, but to confront. His presence alone exposed the atmosphere.

Emotional Fields and the Power of Narrative

Eva Illouz’s, Cold Intimacies sociological insight helps name what Jesus stood against:

“These various actors all converged in the creation of a realm of action in which mental and emotional health is the primary commodity circulated… A great variety of social and institutional actors compete with one another to define self-realization, health, or pathology, thus making emotional health into a new commodity produced, circulated, and recycled in social and economic sites which take the form of a field… The narrative of suffering should be viewed as the outcome of the extraordinary convergence between the different actors positioned in the field of mental health.”¹

Like Solomon’s porch, today’s culture builds emotional fields through media, psychology, education, and politics. These fields do not merely describe emotional pain, they shape identity by marketing pain as a pathway to status or belonging. In these curated fields, to disagree with the approved narrative of self is to be labelled as unwell, unsafe, or unworthy.

But Jesus doesn’t perform for the emotional field. He doesn’t change His message to survive it. He walks through it, in full knowing, full presence, and full freedom.

The Empire of Conformity: Empirical Evidence from Social Psychology

In her critique of the emotional field, Illouz exposes how therapeutic language has been co-opted by state and commercial institutions to regulate identity under the banner of “health.” This, however, is only one layer of influence. Another lies in the empirical study of social behaviour, which consistently reveals how fragile the autonomous self truly is under social pressure.

Social psychologist Elliot Aronson poses a chilling question in Social Psychology:

“But are we, in fact, nonconforming creatures? Are the decisions we make always based on what we think, or do we use other people’s behaviour to help us decide what to do?”²

His question exposes a crack in the modern myth of individualism. We may claim to be free-thinking agents, yet, when faced with consistent peer pressure, our decisions are often driven not by truth, but by consensus. Aronson illustrates this with a striking image: the classroom full of “nonconformist” Apple users, all glowing in unison, each buying into a brand that sold rebellion as a uniform.

But the stakes are even higher. Referencing the mass suicide of the Heaven’s Gate cult, Aronson warns that under sustained social pressure, even the most extreme behaviours can become thinkable.³ This isn’t just a historical anomaly; it’s a window into how powerful the mechanisms of social contagion can be. He writes:

“There is… a more chilling possibility: Maybe many of us would have acted the same way had we been exposed to the same long-standing, powerful conformity pressures.”⁴

In other words, we are not merely influenced by society, we are neurologically, emotionally, and behaviourally shaped by it. What we call self may in fact be the sum total of what others have projected onto us, especially in environments saturated with ideological conformity.

This empirical research aligns seamlessly with the social contagion phenomenon increasingly discussed in gender identity studies, adolescent mental health, and online groupthink dynamics. Just as Illouz unveils the emotional economy, Aronson uncovers the cognitive captivity of living in a socially engineered echo chamber.

And still, Jesus walked out of the crowd. And calls us to follow.

Conclusion:

Jesus was not walking in Solomon’s Porch by coincidence. The Word made flesh never moves arbitrarily. He stood in the very place where human categories and religious systems once defined who belonged and who did not, exposing the fragility of manmade identity scaffolds. And He stood there during the Feast of Dedication, a celebration of the cleansing of the temple after foreign desecration, as if to declare: I am here to cleanse the inner temple, to rededicate the heart, to call My sheep by name, not by label.

In that moment, Jesus became the walking embodiment of a new anthropology and epistemology, a new way of being and knowing. He walked as truth incarnate amid a crowd fractured by speculation, accusation, and division. Some said He had a demon. Others said He opened the eyes of the blind. The same Word of God provoked radically different conclusions. This is the epistemic fault line of the Gospel: the revelation of Christ does not conform to social contagion. It divides precisely because it reveals. It calls the true self to emerge, not from imitation, but from illumination.

To follow Jesus is to be walked out of Solomon’s Porch, out of systems that presume to name us without knowing us, define us without loving us, and confine us without setting us free. Jesus does not conform us to fit in. He transforms us to be made whole. And that transformation often means walking alone, misunderstood, celibate, uncategorised, but never unloved.

In a world drunk on the consensus of emotional fields, algorithms of affirmation, and hashtags that baptise ideology in as truth, Jesus walks ahead, calling each by name, not by trend. To walk with Him is to walk into the freedom of a self not stolen by the crowd.

I have chosen to practice celibacy to honour Jesus. Not only did Jesus continuously show up when partners beat me, cheat on me, and invalidate me, but He did so, so profoundly that He is the love of my life. Legit.

It is this love affair that keeps me seeking to honour Him rather than allowing myself to bow to the contagion of other flawed people like myself naming me when I never gave them that right to do so.

I am, you are, and we are, created by a phenomenal God, who if we take the time to know Him through the Holy Spirit who right here, right now, because of Jesus, we all can walk out of the illusion of categories founded on “Solomon’s Court”.

Practical Application:

We live in a culture that trains us to seek our reflection in the eyes of others. But Christ offers a mirror unclouded by fear, favour, or fashion. The challenge before us is to discern the voice of the Shepherd amidst the noise of the herd.

Practically, this means:

– Ask daily, “Who told me this about myself, and do they have the authority of Christ?” Fast from algorithmic approval: step back from social media affirmations that reinforce false identity scripts.

– Practise spiritual disciplines like solitude, prayer, and biblical meditation, not to earn God’s favour, but to unlearn contagion and relearn communion.

– Refuse to weaponise labels, either against yourself or others. The same Jesus who calls you by name is calling them too.

– Lastly, surround yourself with a community that reflects Christ’s voice, not just your wounds.

Being healed from social contagion is not just about resistance, it’s about reattachment. Reattachment to the voice of God, who still walks in His temple today, searching for hearts not swayed by the mob but stilled by His Spirit.

Prayer:

Father God, we confess that we have often allowed the crowd to name us.

We have conformed to survive, performed to be seen, and believed lies simply because they were loudly repeated. But You, Lord Jesus, walk into our chaos, quiet, present, true.

You call us by name, not category. You do not shame us into change, but love us into freedom.

Let Your voice be louder than our memories, stronger than our wounds, and truer than the crowd.

Holy Spirit, deliver us from social contagion. Teach us to love our givenness, crafted by the Father, restored in the Son, and sustained by You.

May we walk with Jesus out of Solomon’s Porch, into the freedom of being known and named by You.

In Your Holy and Mighty Name Lord, Messiah, King, God, Light, Saviour Jesus,

Amen.

Poetry:

Social Contagion

They

They named me.

Blame me.

Shame.

Infame me.

And growl when they untame me.

They

Surround me.

Mirror-bound me.

Louder still, they sound me,

Until their echo drowns me,

And my no becomes a maybe.

Wear this.

They say where.

Say.

Don’t.

Smile.

Wave.

Accept this.

Cancel that.

And I keep wondering

Who exactly they are.

They

Blur like smoke in mirrors.

Build walls with peers and fears.

Preach inclusion with shears,

Till the soul disappears,

And the body forgets how to spar.

Contagion

It rips through me.

Infection oozes

As insecurity drives me into the herd,

Only to find their social games played all over again:

Love to hate.

Hate to love.

Their breath, viral and sweet,

Whispers: “Be neat, delete, repeat.”

So I shrink my soul for their seat,

Cough up my voice for their tweet,

And wonder when becoming them

Became the only way to survive me.

Contagion politik.

Contagion rhetoric.

Contagion economics.

Contagion psychology.

And some even,

Contagion theology.

It baptises in fear, not fire,

Ordains the crowd as gospel choir.

Their hymns are hashtags,

Their liturgy, likes.

Truth becomes a trending spike,

Then fades beneath algorithmic night.

Universes are lost in their black holes.

Inspiration crushed by uniformity.

A new world order of disorder,

As body parts fill medical waste bins,

Their junk DNA a precursor to estimate life.

Their contagion wallows

On the shallows

Of merth,

And even the weeping willows

Weep no more.

Their roots were severed, truth’s old kin,

Replaced by metrics, votes, and sin.

The willow’s tears were outsourced, drained,

By smiling screens where grief is feigned.

And silence, once a sacred breath,

Now drowns beneath performative death.

Lost in noceboic-dysphoria,

Draped in dystopian chill,

Their slogans a sure tell

Of who they are.

Swallowing me into their they

They,

They named me.

Blame me.

Shame.

Infame me.

And growl when they untame me.

A viral script in cultural skin,

That scripts the outcast and crowns the sin.

Mass-manufactured masks of self,

Stacked like surplus on a shelf.

And in the echo, loud and raw

They infect not with truth, but with the law

Of trend and trauma, fear and fable,

Till even the sane become unstable.

But it is just psychological

Social contagion.

A virus wrapped in virtue’s guise,

Applauded by a thousand lies.

Consensus now the holy creed,

While loneliness and silence bleed.

It dresses in moral panic,

Prescribed in pills,

Marketed as medicine.

And social contagion offers its hand Another capsule

To blur the soul.

To drown out what’s left,

Until all that remains

Is the contagion

Of contagion

Itself.

And I, still breathing, grasp the air,

Searching for a self that isn’t theirs.

But still,

Somehow,

What survives…

Is a self

that isn’t theirs.

ajb ‘25

Footnotes:

1. Eva Illouz, Cold Intimacies: The Making of Emotional Capitalism (Cambridge: Polity, 2007), 68.

2. Elliot Aronson, Timothy D. Wilson, and Robin M. Akert, Social Psychology, 9th ed. (Boston: Pearson, 2010), 229.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.