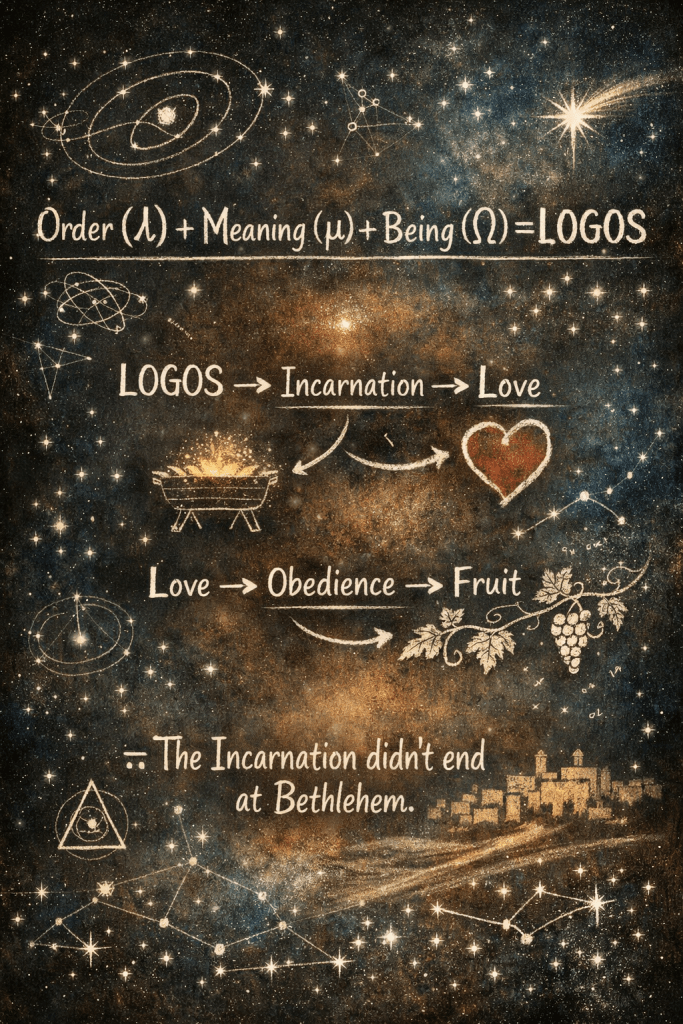

“The logos is that rational or reasoned principle of the universe that permeates and directs all things after its own wise counsel” (Stoic philosophy).

Note from the Author

There are moments when the Holy Spirit’s persistence feels less like a whisper and more like a microwave’s relentless bing! That sacred irritation that refuses to let you rest until you’ve paid attention.

For days now, the Spirit of Truth has been doing exactly that, insisting that I write the Christmas story from a perspective I’ve never quite considered before. Not another sentimental retelling of shepherds and starlight, but a deeper dive into the logic of why the Word became flesh, and why that miracle didn’t end at Bethlehem.

The irony, of course, is that I’m a hairstylist by day. December in retail is hardly the season of silent nights or reflective pauses. Between the buzz of dryers, the swirl of hair clippings, and the endless rhythm of people trying to look their best for Christmas parties, I’ve had little time to breathe, let alone think, conceptualise, construct, and write a Christmas message through an interesting lens.

But the Holy Spirit doesn’t consult our schedules.

This morning, somewhere between caffeine and exhaustion, revelation arrived, not as a booming voice but as a quiet rearrangement of thought. I saw that the Christmas story isn’t just about what happened once.

It’s about what keeps happening whenever the Logos, God’s divine reason, order, and love, takes root in human life and bears fruit.

So this essay, “The Fruit of the Logos: Why the Incarnation Didn’t End at Bethlehem,” is my humble attempt to follow that prompting.

It’s both theology and worship, philosophy and doxology; a tracing of how John’s Gospel reframes everything we think we know about Christmas.

This isn’t an academic exercise for the sake of intellect alone. It’s a pursuit of coherence, the kind of truth that holds both the mind and the heart together.

Because if Christmas is only about a baby born long ago, it’s a beautiful story.

But if it’s about the Logos still being born in us, still speaking, shaping, and bearing fruit through our lives, then it’s the most profound truth the human mind could ever encounter.

So, reader, here we go.

From Bethlehem to now, from Word to flesh, from understanding to becoming, may this reflection invite you not just to admire the Incarnation, but to embody it.

The Forgotten Intellect of Christmas

Christmas is often spoken of as a story to be felt rather than understood. The warm glow of nativity scenes, the carols, the candlelight; all beautiful, but sometimes dangerously disarming. We forget that the Christmas story begins not with sentiment, but with a staggering claim that shook the foundations of Greek philosophy and Hebrew theology alike:

“In the beginning was the Logos.” — John 1:1

To modern ears, Logos sounds like “word.” But to the first-century world, it was a thunderclap. The Logos was the rational structure of reality itself, the principle of coherence, the logic that made the universe intelligible. John wasn’t writing poetic metaphors; he was making a philosophical declaration: the ultimate reason behind everything is not a law or formula, but a Person.

C.S. Lewis once described the Incarnation as “the Grand Miracle,” the moment when spirit and matter, heaven and earth, infinite and finite, fused without confusion.¹ In that single event, divine logic entered the bloodstream of creation. David Bentley Hart calls this the “aesthetic logic of love”: the very beauty of truth revealed as self-giving.²

The early Church Fathers understood this with astonishing intellectual precision. Athanasius wrote that the Word “became man that we might become divine.”³ The Incarnation was not divine improvisation, but divine intention; the Logos stepping into flesh so that flesh might participate in divine coherence.

Theologian John Behr puts it more plainly: “The mystery of Christ is not one event among others; it is the key by which all events are understood.”⁴

Our modern age, however, tends to separate intellect from incarnation. Faith becomes either anti-intellectual emotionalism or sterile abstraction. Both are fragments of the truth but not the truth itself. The Incarnation reunites what we’ve divided: reason and love, knowledge and being, truth and embodiment.

To recover the intellect of Christmas is to realise that God did not suspend logic to enter history; He fulfilled it.

The Word made flesh is not anti-reason; He is reason revealed as relationship.

And so the Christmas story, the birth of the Logos, is not the soft poetry of sentimentality, but the most rigorous metaphysical statement ever uttered: that ultimate reality is intelligent, coherent, and personal love.

The Competing Logoi of the Ancient World

When John declared that “the Logos became flesh” (John 1:14), he wasn’t introducing a new idea into a philosophical vacuum, he was detonating a theological revolution in a world already filled with competing logoi. His words were both bridge and blade: connecting what human reason had long sought, and cutting through centuries of confusion about what ultimate truth really was.

The Greeks had spoken of the Logos long before John ever set pen to papyrus. Heraclitus, writing five centuries earlier, described the Logos as the unseen order governing all things, stating that, “though this Logos is eternal, men always fail to understand it.”⁵ For him, the Logos was an abstract harmony of opposites, an invisible rhythm within chaos. But it was impersonal; the music of the cosmos without a musician.

By the time of the Stoics, Logos had become the “divine fire” permeating matter, the soul of the world itself. Marcus Aurelius urged men to “live according to the Logos,”yet his Stoic god was a rational principle diffused through all nature, not a person who loves, commands, or forgives.⁶ The Stoic Logos explained structure but offered no salvation. It could define virtue, but never deliver grace.

Meanwhile, in the Hellenized Judaism of Alexandria, the philosopher Philo spoke of the Logos as God’s “instrument” of creation, the mediator between the transcendent and the world.⁷ Philo’s Logos came closer to John’s language, but still stopped short of incarnation. It was God’s voice, not God Himself. In all these systems, Heraclitean, Stoic, or Philonic, the Logos remained an elegant abstraction. It ordered, it revealed, but it never loved.

Beyond the Greco-Jewish sphere, the Near East teemed with its own competing logoi. In the pre-Islamic Arab world, the word Allah referred not to the God of Abraham but to a high god among many, one face among the pantheon of astral deities.⁸ These pagan systems, too, claimed coherence: their logos was fertility, power, or celestial cycles. Even eroticism became a kind of metaphysic; temple prostitution in Phoenicia and Babylon was a ritual expression of “cosmic unity.” Here, divinity was reduced to biological impulse.

Against this chorus of metaphysical guesses, John’s proclamation struck like lightning:

“The Logos became flesh, and dwelt among us.”

This was not another speculative logos among many, but the Logos Himself, the eternal source of meaning made personal, visible, and historical. John’s genius was to take the entire vocabulary of the ancient world and turn it inside out. The rational principle behind reality was not an equation, nor an element, nor a detached deity, it was a Person who could be touched, crucified, and resurrected.

Every other logos sought to climb upward toward truth; John’s Logos descended into history to bring truth to us.

Every other logos described order without intimacy; John’s Logos embodied order as love.

Every other logos remained theoretical; John’s Logos became relational.

In one sentence, the Gospel of John dissolved the dichotomy between philosophy and faith. The truth that philosophers abstracted and priests imagined had entered human history with lungs and laughter. And that means the Christmas story isn’t the sentimental fringe of Christian belief, it is the most intellectually subversive claim ever made. The logic of the universe wears a human face.

Jesus as the True Logos

To call Jesus the Logos was not to baptise Greek philosophy, it was to expose its insufficiency. John did not borrow from Heraclitus or Philo; he fulfilled their longing by revealing that what they groped for abstractly had always been a Person.

Every prior logos was an attempt to name coherence without communion. But the coherence of creation was never an impersonal order, it was a communion of divine love.

And so John opens his Gospel not with a genealogy or miracle, but with ontology itself:

“In the beginning was the Logos, and the Logos was with God, and the Logos was God” (John 1:1).

The verb “was” here is not past tense but eternal tense. It locates Jesus not in time but in the ground of being. The Logos is not something God uses; the Logos is God. As Augustine later wrote, “This Word by which all things were made is not a sound in time, but a Power eternal.”⁹

This changes everything.

The Greeks believed that the logos explained why the cosmos existed; John declared that the Logos loved the cosmos He made. The Jews believed God spoke through His word; John said the Word became a man and spoke back.

In Jesus, logic and love kiss. Truth is no longer a proposition to be solved but a Person to be known. And that person, scandalously, commands obedience, not as tyranny, but as friendship (John 15:14–15).

“You are my friends if you do whatever I command you.”

The logic of this is staggering. Friendship with God is not sentimental equality; it is participation in divine coherence. To obey Christ is to align our will with the logic of love that holds all things together.

In philosophical terms, Christ is not only epistemological truth (the ground of knowing) but also ontological truth (the ground of being) and teleological truth (the ground of purpose).

He is the answer to how we know, what we are, and why we exist.

As Colossians 1:17 puts it: “In Him all things hold together.”

Every other logos fractures under this weight. The Stoic logos cannot love; the pagan logos cannot think; the humanist logos cannot save. But the Christic Logos, the Word made flesh, unites reason and redemption in one seamless revelation.

David Bentley Hart calls this “the metaphysical music of grace,” where divine rationality is not cold geometry but self-emptying harmony.¹⁰ And N.T. Wright adds, “If you want to understand what the word ‘God’ means, look at Jesus.”¹¹ That means Jesus is not one truth claim among many. He is the grammar by which all truth claims make sense.

He is not a fragment of the rational order; He is the reason rational order exists. And this is precisely what makes His statement in John 15:16 so astonishing:

“You did not choose Me, but I chose you and appointed you that you should go and bear fruit.”

The Logos who authored creation now authorises human participation in divine purpose. The One who orders galaxies calls us into His logic, not to contemplate it abstractly, but to embody it fruitfully.

To “bear fruit” is not religious productivity; it is ontological alignment. It means to live in rhythm with the structure of ultimate reality, the love that made and sustains all things.

Thus, obedience is not servitude. It is the freedom of coherence, the life of one whose will beats in time with the divine pulse of being itself.

To know the Logos is to think truly.

To abide in the Logos is to live truly.

To bear fruit through the Logos is to love truly.

And that is what the Incarnation accomplished: it brought truth down from God and planted it in human soil.

Bearing the Fruit of the Logos — The Incarnation Continued

John 15:16 doesn’t end with divine election. It ends with divine extension.

“You did not choose Me, but I chose you and appointed you that you should go and bear fruit, and that your fruit should remain.”

This is the moment where theology becomes biography, where the cosmic Logos writes Himself into human storylines.

The Incarnation didn’t terminate at Bethlehem. The Word who became flesh continues to dwell, not in one body, but in many, through those who abide in Him. Christ did not simply enter history; He inaugurated a new anthropology. The human now becomes the instrument of divine logic, the embodied reason of love in a world still tangled in entropy.

Hans Urs von Balthasar called this “the dramatic theology of participation,” that every believer becomes an actor in the divine drama, echoing the Logos through their obedience and creativity.¹² The fruit Jesus speaks of is not moralism or success; it is the visible outworking of divine coherence through a human life fully surrendered to love.

When Jesus commands, “Go and bear fruit,” He is not issuing a moral demand but an ontological invitation. To bear fruit is to manifest the internal logic of the Vine Himself. As sap animates the branches, so divine love animates the disciple. Obedience becomes symphony, the harmony of being rightly ordered to its Source. And this is where philosophy bows to theology:

Plato’s pursuit of the Good, Aristotle’s search for the Prime Mover, and the Stoic quest for Virtue all converge at the foot of a cross. Because there, in that paradox of divine weakness, the Logos bore His own fruit: reconciliation, resurrection, and relationship.

Our fruit, then, is not self-generated virtue but incarnational continuity. We are not moral factories producing good deeds for divine approval. We are branches through whom the Logos continues His work of making creation coherent again.

When Paul writes, “Christ in you, the hope of glory” (Col. 1:27), he’s not speaking metaphorically. He’s describing the ongoing incarnation, the Word continuing to become flesh through human love, forgiveness, truth, and beauty. The Logos bears fruit through us every time reason becomes mercy, logic becomes compassion, and obedience becomes joy. This is why the Incarnation is not just something we celebrate at Christmas; it is something we continue every day.

Every act of truth spoken in love, every choice of integrity in a dishonest age, every moment we embody grace instead of grievance, these are Bethlehem reborn. We become walking annunciations, our lives proclaiming: “The Word is still becoming flesh.”

To bear fruit, then, is not to escape the world but to inhabit it redemptively, to make visible, through embodied logic, the invisible God. The Word was made flesh, and now that Word seeks new flesh to dwell within, yours, mine, ours.

And thus, the Christmas story doesn’t end with a cradle. It continues in every heart that dares to love logically, live truthfully, and act coherently within a disordered world.

The Incarnation was not a one-time miracle.

It was the prototype of every life yielded to the Logos.

The Teleology of the Logos — The Logic of Love and the End of All Things

John begins his Gospel with a beginning, “In the beginning was the Logos.” But implicit in that beginning is also an end. The Logos who authored time is the same Word who will complete it.

Every philosophy of the ancient world searched not only for origin (archē) but for telos, the end toward which all things move. The Stoics said it was cyclical reason returning to itself; Aristotle said it was pure actuality contemplating its own perfection; modern secularism says it’s progress, evolution, or entropy. But in each of these, the story ends either in repetition or dissolution.

Only John’s Logos offers an end that is personal, purposeful, and permanent. The story of the Word made flesh doesn’t close with death but with dwelling, “Behold, the dwelling of God is with man” (Revelation 21:3).

The telos of the Logos is not absorption into impersonal oneness, nor extinction into cosmic silence. It is communion, a world finally coherent because every will, word, and work resonates with divine harmony. The end of all things is not nothingness; it is love fulfilled.

“These things I command you, that you love one another.” (John 15:17)

Love is not a sentimental add-on to divine logic; it is its consummation. The Logos doesn’t merely reveal truth, He reveals that truth is relational, that the structure of reality itself is self-giving love. This means that all true teleology, whether moral, scientific, or existential, must converge here. The purpose of creation is not efficiency, not even knowledge. It is participation in divine love. Everything, from quark to quasar, from human thought to angelic praise, finds its logic and its end in Him.

Thomas Aquinas called this the exitus et reditus, the movement of all things flowing out from God and returning to Him.¹³

The Logos is both Alpha and Omega, origin and orbit, cause and completion. Without Him, there is no rational end because there is no enduring good. As C.S. Lewis once wrote, “He is the pattern, the music, to which all life is to be set.”¹⁴ Therefore, when Jesus says, “You did not choose Me, but I chose you… that your fruit should remain,” He anchors human destiny within divine permanence.

The fruit of the Logos does not decay because it shares the nature of the eternal Vine. Every act done in love, every truth spoken, every mercy offered, every creative spark aligned with divine coherence, is already participating in eternity.

This is why the Incarnation is not a seasonal sentiment but a cosmic revelation. Christmas is not nostalgia; it is ontology. It announces that the logic of love has entered history, and that history’s end is the triumph of that love. At the end of the great story, reason and worship will be one. The Logos who ordered the stars will wipe the tears from every eye. And the fruit of that Logos, every life that abided, every heart that obeyed, every thought made captive to Christ, will remain forever.

This is the teleology of the Logos:

That all logic leads to love,

All love leads to life,

And all life finds its end in Him.

“For of Him and through Him and to Him are all things, to whom be glory forever.” (Romans 11:36)

Epilogue: The Fruit of the Logos — When Logic Becomes Love

It begins in eternity: “In the beginning was the Logos.” And it ends in love: “These things I command you, that you love one another.”

The arc from John 1 to John 15 is the most extraordinary movement in human thought, from ontology to intimacy, from reason to relationship. It is not the cold geometry of divine calculation, but the radiant order of divine communion.

The Greeks sought coherence.

The mystics sought transcendence.

The moderns sought autonomy.

But in Christ, the Logos, coherence, transcendence, and personhood, become one.

Truth speaks, not as principle, but as Person.

And that Person kneels to wash our feet.

This is the scandal of the Logos. The same Word that structured the cosmos now bends low to serve within it. The logic that holds galaxies together holds a towel in His hand. The very reason of existence lays down His life for His friends.

“Greater love has no one than this, than to lay down one’s life for his friends.” (John 15:13)

In that single sentence, Jesus rewrote philosophy. The teleology of being, the purpose of life, is not survival, but surrender.

Not the ascent of the strong, but the descent of the loving.

Not power, but presence.

Not conquest, but communion.

If the Logos is love, then obedience is no longer slavery, it is alignment. To “do whatever He commands” is not submission to tyranny but participation in coherence. It is to live sanely within a universe whose logic is love. And that, in the deepest sense, is what it means to bear fruit.

To let divine order flow through human flesh until logic blossoms into mercy, truth ripens into compassion, and the mind of Christ grows in us like sap in a living branch. When we forgive, create, reconcile, and serve, we are not merely imitating God, we are manifesting the Logos who chose us.

Christmas, then, is not merely a story of birth.

It is the revelation of the world’s architecture.

It is when the invisible logic of creation became visible in a crying child, and that cry has not stopped echoing through human history.

Each generation of believers becomes another Bethlehem, another place where the Word becomes flesh and dwells among us. Every act of love born from obedience is a continuation of the Incarnation. Every truth spoken gently in a deceitful world is the Logos taking on flesh again.

The Fruit of the Logos, therefore, is not an abstract ideal; it is a living reality. It is Christ in us, thinking, loving, redeeming, reasoning, and renewing creation through His people.

And so the story ends where it began:

The logic of God remains love,

The reason for existence remains relationship,

And the glory of God remains human beings fully alive in Him.

“For the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14).

This is the meaning of Christmas.

The Incarnation did not end at Bethlehem, it continues in every life where agape love and truth kiss.

The Logos still speaks.

And the fruit still grows.

Practical Reflection — Living as Branches of the Logos

If the Incarnation continues through us, then thinking rightly and loving rightly can no longer be separated. To “bear fruit” is not a religious metaphor, it’s a metaphysical calling. The Word that spoke galaxies into motion now speaks through human hands, hearts, and habits. This means:

Every act of agape love is cosmic participation. Every truth told is resistance against chaos. Every small obedience is part of divine logic restoring the world.

The Christmas story is not nostalgia; it is invitation. To be chosen by Christ is not privilege; it is partnership in coherence.He doesn’t merely call us friends to soothe us, He calls us friends so that divine intelligence may flow through our will.

So, when you speak gently instead of harshly, you are bearing the fruit of the Logos.

When you create beauty in a world addicted to noise, you are bearing the fruit of the Logos.

When you forgive someone who does not deserve it, you are bearing the fruit of the Logos.

When you choose truth over popularity, peace over pride, mercy over mockery, the Incarnation continues.

The Christian life is not about escaping the world but embodying divine coherence within it. The goal is not perfection, it is participation. It is to let the Word that became flesh continue to dwell richly in us, until love itself becomes the logic of our lives.

This is the fruit that remains.

Prayer — The Logic of Love Made Flesh

Father, Son, and Holy Spirit,

We stand in awe before the mystery that You, the infinite Logos,became flesh, reason wrapped in mercy, truth wrapped in love.

Forgive us when we reduce You to sentiment, when we speak of Your birth but not of Your logic, when we celebrate without understanding the world-shifting coherence You brought to being.

Teach us again that the Incarnation is not a moment but a movement, that You are still being born in every act of compassion, every truth spoken with courage, every surrender that says, “Not my will, but Yours.”

Let our minds be renewed until they think in Your rhythm.

Let our hearts be reshaped until they love in Your pattern.

Let our words and works be so aligned with You that our lives become living logic, truth in action, reason in mercy, obedience in joy. May we be the branches through which Your Word continues to take on flesh. May the fruit of our lives remain, because it was grown from You, the True Vine.

And as we walk toward another Christmas, may we not simply remember Bethlehem, but become it.

In the Magnificent, Holy and Invincible name of Jesus Christ, the Logos made flesh,

Amen.

TRACK TO ENJOY:

References

1. C.S. Lewis, Miracles (New York: Macmillan, 1947), ch. 14 “The Grand Miracle.”

2. David Bentley Hart, The Beauty of the Infinite (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), p. 153.

3. St. Athanasius, On the Incarnation, §54.

4. John Behr, The Mystery of Christ: Life in Death (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2006), p. 37.

5. Heraclitus, Fragments B50, B90 (Diels–Kranz).

6. Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, V.32.

7. Philo of Alexandria, On the Creation of the World, §§24–25.

8. Karen Armstrong, A History of God (New York: Ballantine, 1993), pp. 33–35.

9. Augustine, Tractates on the Gospel of John, I.13.

10. David Bentley Hart, The Beauty of the Infinite, p. 205.

11. N.T. Wright, Simply Christian (New York: HarperOne, 2006), p. 118.

12. Hans Urs von Balthasar, Theo-Drama, Vol. II: Dramatis Personae (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988), pp. 270–273.

13. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, I q.44 a.1.

14. C.S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory (New York: HarperOne, 2001), p. 45.