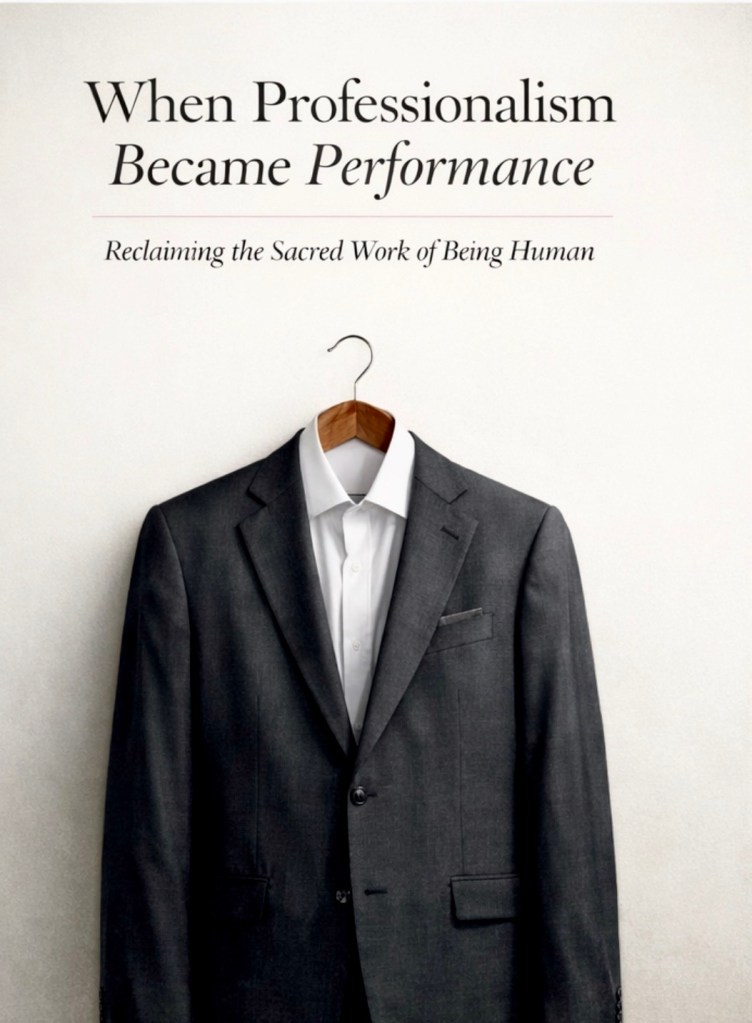

The Mask We Call Work

The meeting began, as they all do, with polite smiles and muted microphones.

Someone joked about the weather; another nodded at their screen as if it were a mirror that could confer belonging. Beneath the fluorescent hum, every face carried the same exhausted choreography; professional poise, digital etiquette, the unspoken contract that we will all pretend to be fine.

This is the modern liturgy of work.

We sit in glass rooms or behind glowing rectangles and perform composure. We adjust our tone to “professional,” our language to “appropriate,” our emotions to “manageable.” The hierarchy hums like background noise; everyone knows when to laugh and when to mute. We have learned to polish our humanity until it looks like competence.

Somewhere along the line, professionalism stopped being about excellence and started being about image.

It became less about what we contribute and more about what we signal, how well we master the semiotics of success. Our CVs and LinkedIn posts have become the modern Psalms of self-promotion: carefully curated testimonies of our measurable worthiness. The workplace no longer asks, “Who are you?” but rather, “How well can you perform the part?”

We weren’t always like this.

There was a time when vocation meant calling, a sacred summons to participate in something larger than ourselves. Work was once prayer, craft was once devotion, and skill was once love in motion. Now, we call that output.

Professionalism has turned from stewardship into performance; from calling into costume. We trade soul for salary, truth for tone, presence for polish.

And perhaps the saddest part is how ordinary it feels.

We no longer notice the ache of the mask because everyone is wearing one.

The Birth of Professionalism

To understand how professionalism became performance, we have to trace it back to when it was still a matter of character rather than presentation.

The roots of professionalism stretch deep into the soil of 18th- and 19th-century industrialisation, when Europe and America were reconfiguring the meaning of labour. Factories, bureaucracies, and emerging middle classes birthed a new ideal, the professional, someone distinguished by expertise, order, and moral reliability. It was the antidote to chaos, the social covenant of trust in a world being mechanised.

But this ideal didn’t come from the boardroom; it came from the pulpit.

Max Weber famously traced the rise of professionalism to what he called the Protestant work ethic, the idea that work itself was an act of worship, a visible expression of invisible grace. In Puritan theology, vocation (from vocare, “to call”) was a divine summons to serve God through one’s craft. Work wasn’t simply how one survived; it was how one glorified.

As the centuries turned, this sacred thread began to fray.

What began as devotion transformed into duty, and duty slowly ossified into decorum.

By the Victorian era, professionalism had become a moral badge, a sign of respectability, of civility, of being the right kind of person. Richard Sennett, in The Craftsman, argues that craftsmanship once tethered morality to mastery, doing something well for its own sake. But when work was industrialised, that tether snapped. The craftsman became the clerk, and the spirit of vocation was replaced by the bureaucracy of productivity.

By the dawn of the 20th century, as Charles Taylor would later describe in A Secular Age, the sacred canopy that once covered vocation had been replaced by the fluorescent light of efficiency. The professional no longer worked unto God but under management.

Integrity gave way to image; moral substance gave way to procedural compliance.

Professionalism, once a covenant, became a costume.

And though it promised dignity, it quietly planted the seeds of our modern alienation, that subtle ache that comes when doing becomes detached from being.

The Shift: From Vocation to Persona

If the industrial age gave us the professional, the late twentieth century taught that professional how to perform.

The shift began quietly, under the fluorescent glow of open-plan offices and corporate branding campaigns that promised empowerment while scripting every emotion. Professionalism evolved from a moral framework into a managed identity, something to curate, optimise, and market.

Sociologist Arlie Hochschild, in The Managed Heart (1983), named this phenomenon emotional labour: the selling of one’s authentic affect for institutional gain. Flight attendants, call centre workers, salespeople, all trained not merely to do the job, but to be the brand. A smile became policy; warmth became protocol. What was once the genuine overflow of character became the staged management of mood.

But the logic of emotional labour did not stay in airports or corporate offices. It seeped into every domain of modern life. Erving Goffman, in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956), foresaw this when he described society as a stage, each of us performing roles before various “audiences,” switching scripts depending on who was watching.

By the time the twenty-first century arrived, social media had perfected Goffman’s metaphor into a business model. The “professional persona” migrated online, where image eclipsed integrity entirely. We began to live, as Shoshana Zuboff observes in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (2019), in an economy where human experience itself became raw material, every thought, emotion, and aspiration mined, measured, and monetised. The office that demanded masks morphed into a world that became one.

Emails demanded the “appropriate tone.”

HR departments trained staff in “emotional intelligence” while suppressing dissent.

LinkedIn baptised self-promotion as virtue.

Authenticity became a corporate slogan precisely because it had become impossible.

We no longer simply worked; we performed working.

We didn’t only communicate; we curated communication.

The professional, once a person of mastery, had become a persona of manageability. And in the process, something sacred slipped away, the soul’s capacity to encounter work as calling. We had become experts at looking composed and total strangers to feeling whole.

The Theological and Anthropological Cost

At its root, professionalism is not just a sociological phenomenon. It is a theological tragedy.

Humanity was never created to perform image but to bear it.

To be professional once meant to profess something, to declare with life and labour a truth greater than oneself. But as our culture severed vocation from transcendence, “profession” collapsed into mere performance. The professional mask is no longer a tool of craft; it has become a mechanism of concealment.

In Genesis 3, the first humans, newly aware of their nakedness, sewed fig leaves to hide from one another and from God. The moment shame entered the world, image management was born. What we now call “professionalism” is, in many ways, the industrialised descendant of those fig leaves, a system of refined concealment designed to preserve dignity while distancing intimacy.

We have become fluent in the language of competence and illiterate in the dialect of confession. We wear professionalism as a moral costume, not because it expresses truth, but because it protects us from exposure.

Kierkegaard, in The Sickness Unto Death, described despair as the condition of being divided from oneself; the refusal to be the self that God created. In modern workplaces, that despair is institutionalised. The “Work-Me,” “Home-Me,” and “Faith-Me” fragment the soul into role-based selves, each optimised for context but estranged from coherence.

When Jesus says in John 15:15, “I no longer call you servants, but friends,” He dismantles the transactional distance between doing and being. Friendship with God replaces function with fellowship. Yet modern professionalism reintroduces the distance Christ died to remove. It reinstates servanthood to system over sonship to Spirit.

The cost of that disconnection is immense.

Theologically, it distorts the Imago Dei, the idea that human beings reflect God’s nature through relational presence, creativity, and love. Anthropologically, it reduces the person to performance metrics, depersonalising the very thing that makes us divine image-bearers: our capacity for communion.

Professionalism tells us: “Be consistent.”

The Gospel whispers: “Be whole.”

When consistency becomes a substitute for authenticity, and performance replaces presence, we lose the ability to experience grace in the place we spend most of our waking hours. And what began as a desire to serve well quietly mutates into a fear of being seen. Or a “thing” that keeps a job to pay the bills. A typological plug-n-play with a heart beat.

The Collapse of the Mask (Modern Burnout & Identity Crisis)

Every mask eventually cracks, even the professional one.

Burnout, we are told, is a logistical problem: too much work, too little rest. But beneath the spreadsheets and sleep deprivation lies something deeper: an ontological exhaustion. We are not merely tired; we are divided. The corporate world calls it “fatigue.” Scripture calls it futility, the slow unraveling of meaning when what we do no longer reflects who we are.

In the late 20th century, psychologists began to diagnose what was happening to millions: perfectionism-induced depersonalisation. The professional mask, once a symbol of reliability, became an instrument of alienation. We learned to fake-smile through collapse, to use competence as camouflage for despair.

Christina Maslach’s seminal work on burnout described it as “a crisis in self-identity.” It isn’t merely about overwork; it’s about over-performance, the dissonance between outer function and inner truth. The human being, designed for communion, suffocates under constant curation, sales targets, performance appraisals, and emotional manipulative sloganeering such as “If you love what you do, you will never work a day in your life.” Performed “love” becomes the bully we enact to convince ourselves that our self is fully reflected in our doingness.

The irony is cruel, the more we pretend the image of composure, the less we recognise the image of God. The more we perform connection, the lonelier we become.

Corporate culture now markets authenticity as a strategy; mindfulness seminars, wellbeing apps, “human-centred” branding. Yet each one only deepens the performance. As Zuboff observed, we have entered an age where even vulnerability is monetised.

And the church is not immune. We baptise the same performance with religious vocabulary: “excellence,” “decency and order,” “representing the kingdom.” But beneath the language, the exhaustion is identical. Our ministry teams burn out, not for lack of faith, but because they confuse servanthood with stagecraft.

The professional self collapses not simply because it is tired, but because it was never meant to hold the weight of the soul. The human heart was not designed to sustain perpetual applause.

We were made for rhythm, not performance.

For Sabbath, not show.

For presence, not presentation.

When the façade finally fractures, when our curations can no longer contain our longings, we encounter what Kierkegaard called “the sickness unto death,” not the end of life, but the end of pretending.

And that is the strange grace of collapse. Because the death of the mask is often the birth of the person.

Redemption: Reclaiming Vocation as Relationship

If professionalism fractured us into personas, redemption invites us back into presence. Vocation, at its truest, was never meant to be a role we play, it was a relationship we live.

When Dorothy Sayers wrote Why Work? (1942), she argued that work was not primarily a thing one does to live, but “the thing one lives to do.” Not for the sake of identity performance, but as participation in divine creativity. “The only Christian work,” she said, “is good work well done.” Not because it earns favour, but because it reflects favour already given.

This is the quiet revolution of Jesus, the unprofessional God who knelt to wash the feet of those who would later betray Him.

He did not curate image; He incarnated truth. His excellence was not performance but presence, holiness made human, humility made divine. In Him, vocation is restored to its proper order: not as an instrument of self-advancement, but as a language of love. The carpenter’s bench becomes altar. The spreadsheet becomes prayer. The task becomes transfigured when done in communion rather than competition.

Eugene Peterson described this as “the holiness of the ordinary.”

Christ plays in ten thousand places, in the meeting room, the classroom, the kitchen, the salon, wherever human hands meet divine purpose. The sacred and the secular were never meant to be separate stages; only a single life, fully lived in God.

When Jesus says, “Abide in Me” (John 15:4), He does not invite us to a performance review. He invites us home. Holiness is not the perfection of our conduct; it is the coherence of our being; the end of fragmentation, the healing of divided selves.

To work “in His name” is to participate in His presence, to do what we do as if He were doing it through us. And when that happens, professionalism becomes something entirely different. It ceases to be a performance of self and becomes an offering of service.

Professionalism becomes love with structure.

Excellence becomes worship with skill.

And vocation becomes the echo of Eden, where what we do and who we are finally agree. Because redemption is not merely forgiveness of sin. It is the restoration of form, the reuniting of function and fellowship, skill and spirit, labour and love.

The Courage to Unmask

At some point, every performance reaches its curtain call. The lights dim, the audience fades, and what remains is the person behind the posture, the one God has been trying to reach all along.

We call that moment burnout, breakdown, reinvention.

He calls it invitation.

Because before God uses us in public, He heals us in private. And healing begins where pretending ends. To walk unmasked into the world of professionalism is not rebellion, it’s resurrection. It’s the quiet defiance of a soul that refuses to trade presence for polish, or truth for applause.

The modern world worships image, the “professional look,” the curated tone, the acceptable faith. But Christianity was never a performance of moral competence; it was the raw, often uncomfortable presence of divine love lived out in human imperfection.

Jesus did not die for our professionalism, He died for our personhood.

When we return to that truth, everything changes.

Work becomes worship.

Colleagues become neighbours.

Deadlines become discipleship.

The sacred sneaks back into the secular, and even the boardroom becomes Bethlehem, a place where the invisible God chooses again to take form in flesh. To be holy, then, is not to be flawless; it is to be whole. To no longer divide yourself between the role you play and the person you are. It takes courage to live that way.

Courage to say, “I don’t know,” in a culture that rewards certainty.

Courage to confess, “I’m struggling,” in an economy that commodifies success.

Courage to remember that you were made for communion, not competition.

The courage to unmask is not the courage to be reckless, it is the courage to be real. To let love, not image, define what professionalism means. Because in the Kingdom, excellence is never performance; it’s participation. And holiness is never the absence of flaw; it’s the presence of love.

So as we walk into 2026, may we dare to be less impressive and more incarnate.

Less polished, more present.

Less professional, more profoundly human.

Because professionalism without presence is noise.

Presence without performance is trust.

And maybe holiness at work begins, truly begins, where the mask finally falls off.

Prayer

Father God, Jesus, Holy Spirit

You who shaped the stars and still stoop to wash feet, teach us again the holiness of the ordinary. Forgive us for every time we traded truth for polish, for every mask we’ve worn to seem acceptable, and for every moment we’ve forgotten that presence is the only professionalism You ever required.

Take our craft, our labour, our skill, and breathe into them the pulse of eternity. Let our hands become instruments of love, our words agents of peace, our excellence an echo of Your grace.

Where we have performed, make us authentic.

Where we have hidden, make us whole.

Where we have exhausted ourselves trying to seem worthy, remind us that we already are, because You are.

May our workplaces become sanctuaries, our tasks become prayers, and our integrity become testimony.

And when the masks grow heavy, teach us again the courage of the unmasked Christ, the One who knelt, served, and saved without image management.

In Your Holy and Beautiful Name, Messiah, King, Lord Jesus,

Amen.