A Scholar’s “god” or the God Who Speaks? (John 9:24–25)

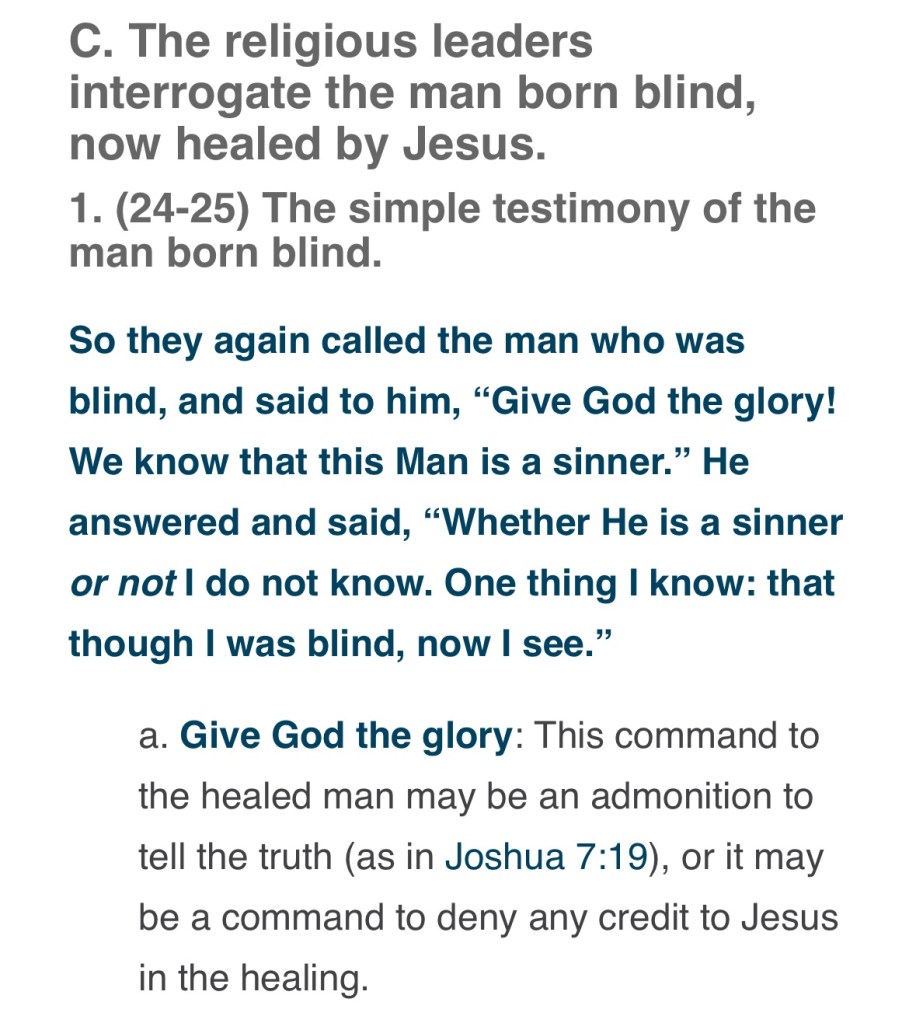

“Give glory to God! We know that this man is a sinner.” The phrase ricochets with presumed-knowledge’s epistemic finality. Spoken not by outsiders or atheists, but by the religious elite of Jesus’ day, it reveals something deeper than counter-belief, it reveals control. A cognitive posture that anchors truth not in revelation, but in institution. In John 9:24–25, the once-blind man replies not with theology but with encounter: “Whether He is a sinner I do not know. One thing I do know, that though I was blind, now I see.” His testimony ruptures the authority of sanctioned knowledge.

This is not merely a confrontation between miracle and misinterpretation, it is a clash between lived truth and preapproved truth. The Pharisees’ “we know” mimics the epistemic gatekeeping of power structures across history. Their certainty is not built upon divine encounter, but on ritual observance. They are defenders of what Karl Barth might call a religious system built on humanity’s attempt to ascend to God, rather than receive revelation from the God who descends to us in Christ.¹

The man’s defence is not an argument, it is an interruption. Like Daniel in Babylon, who refused to direct his prayers to institutional idolatry, this man refuses to conform his voice to collective certainty. Both Daniel (Daniel 6:1–13) and the healed man confront the same accusation: disobedience to the officially approved form of knowing God. Yet both are vindicated not by rhetoric, but by the reality of divine intervention. Epistemological arrogance meets humble revelation, and loses.

We live in a world where the scholar’s god often bears more resemblance to ourselves than to YHWH. A god domesticated by peer review, defined by abstraction, and accessible only through elite discourse. Yet the God who speaks, who heals, who interrupts, who weeps and breathes, is not confined to the libraries of prestige. He is heard by the blind beggar. Known by the outsider. Revealed not in theory but in presence, and disruption.

The Scholar’s God – Knowledge as Control

https://philarchive.org/archive/IVARCI

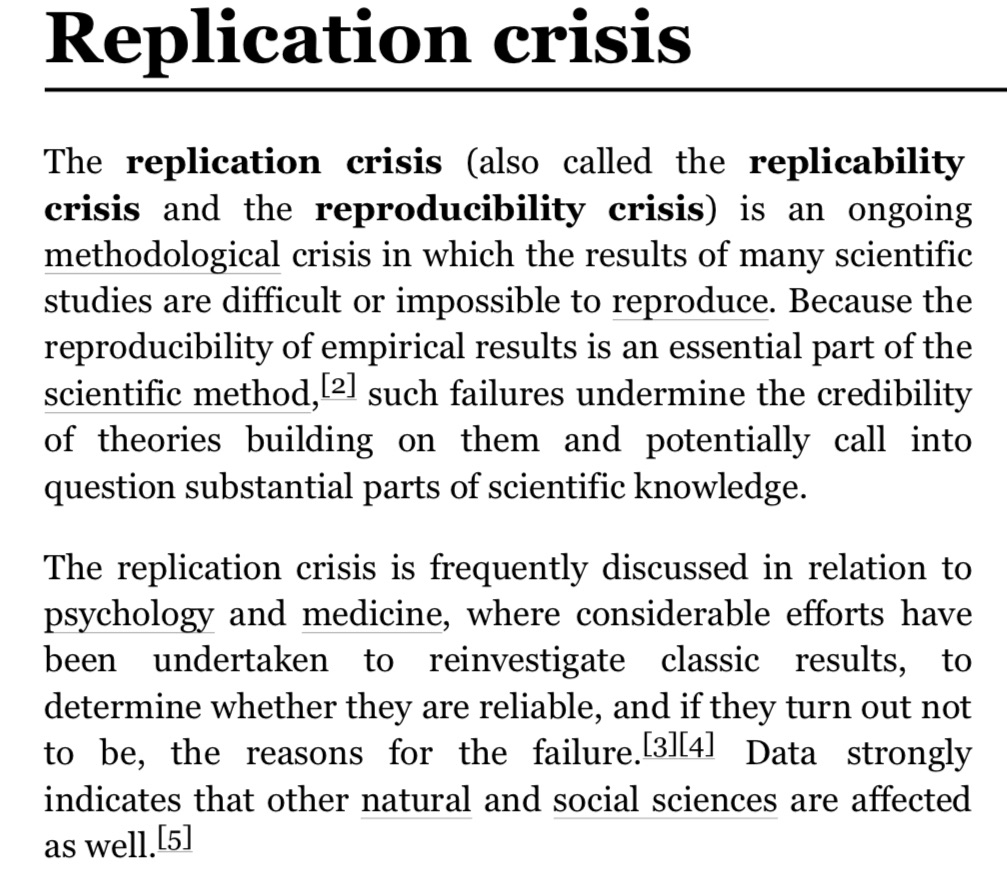

The assertion “We know that this man is a sinner” (John 9:24) is not just religious language, it is an epistemological stronghold. It speaks from within a framework where authority is defined not by the voice of God but by the sanctioned interpretations of a scholarly or priestly elite. In the ancient world, the Pharisees held theological jurisdiction. Today, the academy often performs a similar function. It enthrones systems of inquiry that prize abstraction over incarnation, and certainty over witness. The result is a God of credentials, a domesticated deity who must pass peer review before He can be acknowledged.

This phenomenon is not unique to theology. Jacques Ellul warned that the modern obsession with technique and systematisation has led to a technological society where efficiency becomes the arbiter of truth. Knowledge becomes a commodity, stripped of awe and surrendered to utility.² In such a world, divine encounter is marginalised, not because God has become less real, but because revelation refuses to be managed.

Philip Rieff, in his seminal The Triumph of the Therapeutic, observed that modern culture has replaced sacred order with psychological well-being.³ What is called truth must now pass through the lens of personal affirmation and institutional validation. In this climate, revelation that unsettles the self, or challenges academic consensus, is suspect by default. Rieff’s diagnosis aligns chillingly with the posture of the Pharisees: if the act of God does not conform to our system, it must be rejected.

Yet Scripture refuses to submit to institutional control. The prophets were not tenured lecturers; they were often exiles, poets, or madmen by the standards of their day. Jesus, too, was not a graduate of the rabbinical schools. Walter Brueggemann argues that the prophetic voice functions against the totalising narratives of empire. It names the pretensions of control and offers a counter-narrative of divine freedom.⁴

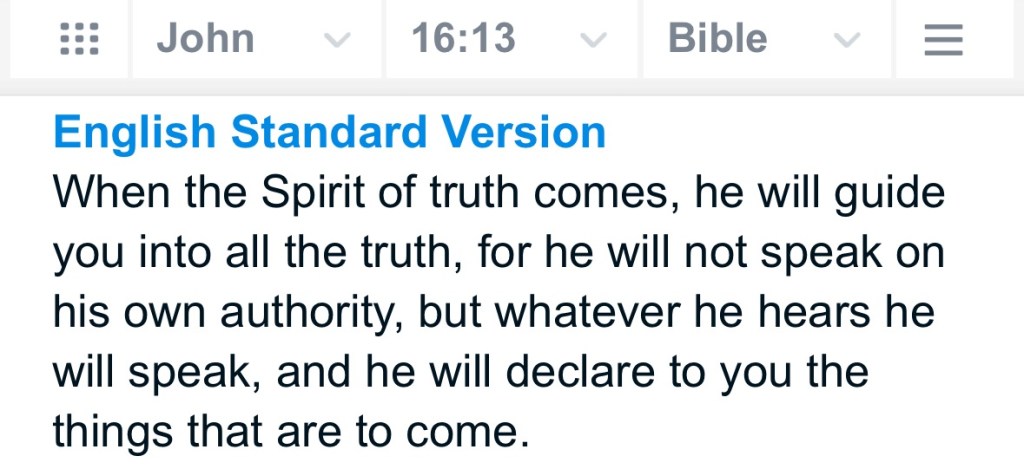

To “know” in the biblical sense is relational, not merely analytical. But the scholar’s god knows only in concepts, not communion. The God of Scripture, by contrast, speaks, often unexpectedly, often uncomfortably, but always personally. As Abraham Heschel notes, “The prophets are not just inspired; they are invaded.”⁵ Revelation is not a passive download, it is a divine rupture. And it remains uncontrollable.

When Systems Silence the Divine Voice

The accusation hurled at Jesus, “We know that this man is a sinner” (John 9:24), reveals more than suspicion. It exposes a tragic irony: those most familiar with God’s words were deaf to His voice. The religious leaders, bound by their interpretive systems, could not comprehend a God who acted outside their sanctioned categories. Like the officials in Daniel’s day, who weaponised legal frameworks to trap Daniel in worship (Dan. 6:5), they redefined piety in a manner that protected institutional sanctity but muted divine spontaneity.

This is not merely an ancient dilemma. Wade Mullen’s research on institutional responses to whistle-blowers in Christian contexts shows how systems built to preserve God’s truth can become complicit in hiding it. His PhD dissertation details how language, policy, and leadership often collude to suppress uncomfortable revelations, punishing the one who sees rather than reforming the one who sins.⁶ In this dynamic, the healed man in John 9 becomes a liability, an epistemological threat to the religious consensus. He must be discredited or expelled, lest the system itself be indicted.

James Cone writes, piercingly, that such systems are not neutral; they are ideological and racialised. His work The Cross and the Lynching Tree argues that religious institutions in America, especially white churches, often turned away from Christ’s crucified solidarity with the oppressed, opting instead to serve the interests of empire.⁷ Cone’s critique is more than historical, it is prophetic. Systems built around power will always view divine revelation with suspicion when it arrives through the marginalised.

This silencing is not just sociological; it is spiritual. Sarah Coakley identifies the subtle temptation to substitute theological discourse for divine encounter. In her exploration of prayer, power, and contemplation, she warns that the Spirit’s voice is often drowned out by the noise of institutional legitimacy.⁸ Theology becomes an echo chamber. Spiritual formation becomes an academic checklist. Revelation is reduced to redundancy.

Tricia Lott Williford’s memoir You Are Safe Now speaks from the underside of such systems. In recounting her journey through grief, trauma, and spiritual awakening, she writes, “Sometimes the voice of God is the only thing that doesn’t make sense—and yet the only thing that saves.”⁹ Her experience affirms that the divine voice still calls, but it often does so from outside the camp, beyond the syllabus, beneath the noise.

The man born blind was healed by God but interrogated by those who claimed to know God best. His testimony threatened the scaffolding of control. He could not explain the miracle, but neither could he deny it. “One thing I know,” he said, “that though I was blind, now I see.” In that moment, theology was not in the mouths of the credentialed, but in the witness of the once-forgotten.

When Certainty Replaces Communion

The Pharisees’ declaration, “We know that this man is a sinner,” speaks with unflinching certainty (John 9:24). But theirs is not the certainty of communion; it is the certainty of control. It reveals how religious institutions, like all systems of power, are often more committed to interpretive mastery than relational surrender. They weaponise knowledge as a boundary, not as a bridge. As Eugene Peterson writes, “The moment the word is depersonalised into an idea or a truth or a principle, something essential is lost, the relationality of revelation.”¹⁰

Jacques Ellul, in The Humiliation of the Word, contrasts the visible and the invisible, the explainable and the relational. He warns that our obsession with clarity, evidence, and verbal precision can eclipse the revelatory mystery of the living Word.¹¹ What cannot be diagrammed is dismissed. Yet, the God who speaks also withholds. He dwells in unapproachable light and communes through veiled presence, not institutional consent.

Stanley Hauerwas similarly critiques the modern theological project as one driven by the idol of certitude. “The task of the theologian,” he writes, “is not to make God make sense but to help the church be faithful.”¹² When theology becomes a tool for system preservation rather than spiritual pilgrimage, it ceases to be theology at all. The blind man’s experience becomes problematic because it resists theological packaging. He cannot cite the correct rabbis or explain Sabbath nuance, he can only testify to encounter.

Karl Barth, who refused to build his theology on human ascent to God, insisted that “God is known only because God makes Himself known.”¹³ For Barth, divine self-revelation shatters the scaffolding of human religion. In that sense, John 9 is not about healing only, it is about dismantling the illusion of theological control. The religious leaders had systematised God into obedience, moralism, and exclusion. But Jesus, as the Word made flesh, reveals a communion that precedes comprehension.

In many churches today, the spirit of the Pharisees lives on. We baptise epistemological certainty as faith, confuse intellectual assent with trust, and replace the mystery of encounter with the mechanics of ritual. Yet, communion is not born of control. It is born of vulnerability, of Spirit-led proximity to the Christ who spits in mud and breaks Sabbath for the sake of one forgotten man. The man who could not see is now the only one who does.

When God No Longer Fits Our Frameworks

“Give God the glory! We know this man is a sinner” (John 9:24). These words expose a crisis. When divine activity no longer fits within the authorised framework of institutional religion, it is not the framework that is interrogated but the person through whom God acts. The healed man’s testimony is problematic not because it lacks clarity but because it disrupts the sanctioned order. Power, after all, prefers predictability.

Wade Mullen, in his study of abusive religious systems, shows how institutions often mask their fragility behind moral outrage and rehearsed narratives. When control is threatened, spiritual leaders may resort to discrediting, silencing, or reinterpreting dissent.¹⁴ “Authoritative systems often shape perception by controlling what stories may be told and how,” he explains.¹⁵ The Pharisees, by labelling Jesus a “sinner,” were not merely stating doctrine; they were preemptively framing the narrative to maintain their interpretive monopoly.

Tricia Lott Williford, reflecting on her experience of spiritual trauma, states, “I felt God move in ways that no one had given me permission to recognise.”¹⁶ This is the dilemma of authentic spiritual encounter: it disrupts. A God who speaks may also contradict us. A God who heals may do so outside our categories. In both cases, we are faced with the terrifying invitation to relinquish control.

James Cone, writing out of the Black American theological tradition, issues a prophetic rebuke to frameworks that domesticate God. “If God is not identified with the oppressed and their struggle for justice, then we must reject that god,” he insists.¹⁷ This is not a sentimental declaration, it is a theological demand for integrity. When systems of privilege create a deity who validates injustice, then the true Biblical God must be found elsewhere, among the crucified, not the comfortable.

This is precisely the tension Jesus provokes in John 9. His presence does not affirm the authority of the synagogue; it confronts it. He heals in unpermitted ways. He empowers voices previously unheard. And in doing so, He threatens the integrity of a system that claims to speak for God but refuses to listen to Him. The man born blind now sees, and because he sees, he must be silenced by the institution.

The Testimony That Cannot Be Tamed

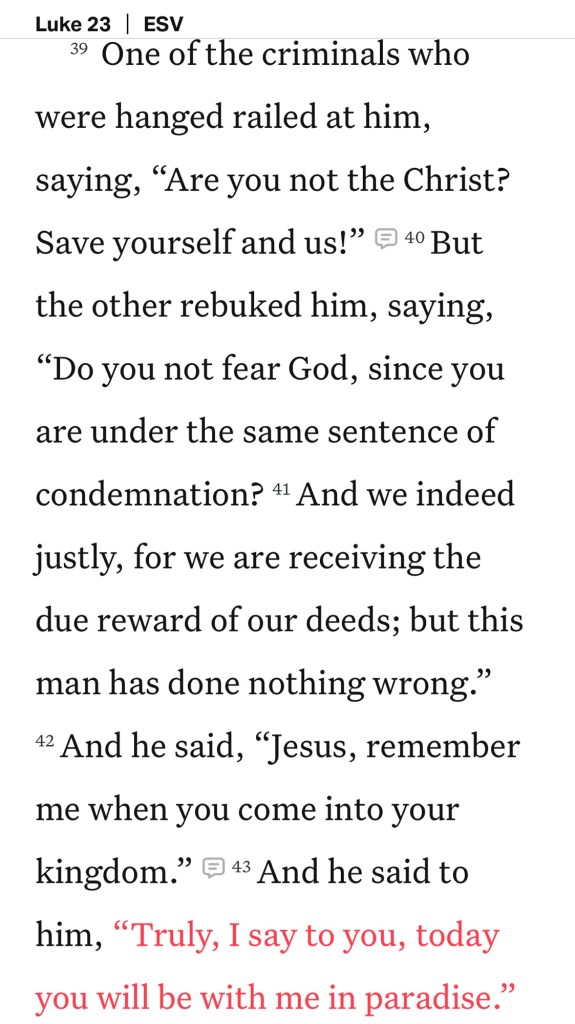

At the heart of John 9 is not merely a healing, but a confrontation between lived experience and institutional control. The man born blind becomes a disruptive witness. His sight exposes the knowledgeable’s lack thereof. This phenomena of academic bias is affirmed in 2 Corinthians 3:14, “But their minds were hardened. For to this day, when they read the old covenant, that same veil remains unlifted, because only through Christ is it taken away.” When commanded by the Pharisees to conform, “Give glory to God! We know this man is a sinner,” he refuses to echo the dominant theological script. His testimony violates every rule of scholarly discourse. It is not peer-reviewed, systematised, or hierarchically sanctioned. But it is true. So do the accounts of Rahab, Mary the adulterer, Hosea’s wife, and the entire history of the Israelites confirm the mercy of God who speaks, versus institutional interpretations of God. So does the account of the forgiven thief on the cross.

Wade Mullen’s work on institutional abuse reveals how manipulative systems seek to dominate the narrative. Organisations and leaders often deploy what he terms “image repair tactics” to discredit whistle-blowers and marginalise witnesses. “The abuser,” he writes, “must ensure that the truth-teller appears untrustworthy,” not because the testimony is false, but because it is unmanageable and incompatible with the curated image of authority.¹⁸ The healed man’s voice, like Daniel’s unsanctioned prayers, becomes a threat to the machinery of legitimacy.

Similarly, Jacques Ellul warns that modern societies elevate the technique of control, not merely of machines, but of thought, language, and even faith itself. What cannot be predicted or programmed is seen as destabilising to the social order. “Wherever testimony is no longer valued, only verification remains. And verification, though useful, cannot lead to truth.”¹⁹ The man born blind cannot “verify” Jesus’ status according to the Pharisees’ method, but he bears witness nonetheless.

This is the danger of a scholar’s god: one who fits within intellectual parameters and can be confined within philosophical categories. As Karl Barth reminds us, theology must never become a mirror for our own ideas. “The Word of God,” Barth writes, “always comes from outside. It interrupts, it judges, it redeems.” And it comes, above all, through encounter.²⁰ This is what the religious elite in John 9 could not abide, a divine revelation that bypassed their hermeneutics.

Abraham Heschel echoes this prophetic warning: “Faith is not the clinging to a shrine but the endless, trembling openness to the voice.”²¹ The voice of Jesus was not delivered through temple scrolls or academic discourse, but through the body of a once-blind beggar whose only qualification was that he saw.

In that sense, the healed man’s defiance is not arrogance, it is liturgy. It is the embodied proclamation of a God who speaks for Himself, not through systems, but through scars. His voice cannot be tamed. And those who try to silence the testimony only reveal how little they can hear.

Practical Application: Dismantling the Institution Within

It is easy to critique systems “out there,” governments, religious bodies, or academic frameworks. But John 9 demands a more unsettling reflection. The Pharisees were not villains in their own eyes; they were guardians of theological fidelity, trained in the law, convinced of their orthodoxy. Their error was not ignorance, but entrenchment. Their refusal to hear Jesus was not due to lack of exposure, but an inner allegiance to control, predictability, and institutional order.

We must ask:

Where do we behave like the scholar’s Pharisee?

Where have we built inner temples of certainty so secure that the living God cannot disturb us?

Where do we drown out the voice of Christ with our need to be right, respectable, or revered?

The scholar’s god is not merely a public idol; it is a private fortress. Handball 2:18 alludes to this, “What profit is an idol when its maker has shaped it, a metal image, a teacher of lies? For its maker trusts in his own creation when he makes speechless idols!” We create idols when we quote Scripture yet ignore the Spirit. We defend orthodoxy while suppressing encounter. We replace the unpredictability of grace with the reliability of systems, psychological, theological, or relational. And like the Pharisees, we risk silencing Jesus precisely when He is speaking loudest: through interruption, through outsiders, through revelation we cannot manage.

To walk free from the scholar’s god is to embrace humility over certainty, listening over explaining, repentance over control. The healed man in John 9 was not catechised, but he was available. He simply bore witness. And perhaps that is the invitation: to let go of explaining God, and return to encountering Him.

Conclusion: From System to Surrender

If John 9 teaches us anything, it is that divine revelation rarely comes to those who have already made up their minds. The religious leaders “knew,” and so they could not see. The healed man did not know, and so he could. The irony of this story is that the one blind from birth ends with vision, while those entrusted with sacred insight become the most spiritually blind.

We must acknowledge the quiet violence of our internal institutions: the walls of pride we erect, the echo chambers we live within, the theological algorithms we run that keep us from encountering God on His own terms. The scholar’s god is safe, explainable, and silent. But the God who speaks? He is disruptive, personal, and calls us to follow; not theories, but Him.

To hear God again, we must become blind to what we thought we saw. We must surrender our academic idols and let mystery lead us to worship. We must stop polishing the stained-glass of our intellect long enough to see the tear-streaked face of Jesus looking back at us. And we must ask: will we cling to the god of our understanding, or follow the God who heals in ways we can neither predict nor control?

Prayer

Lord Jesus,

Disrupt our certainty. Break down the institutions within us that have replaced Your living voice with our own confidence.

Forgive us for defending ideas of You while resisting Your presence. Help us to hear You, not as a theory, not as a system, but as the God who still speaks.

Where we have made idols of intellect, where we have silenced You with analysis, where we have feared Your interruption more than loved Your presence, we repent.

Teach us again to follow. To tremble when You speak. To let go of what we think we know. And to stand, like the once-blind man, saying only this: “One thing I know: though I was blind, now I see.”

In Your Holy Name Messiah King Jesus,

Amen.

References

1. Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, ed. G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance, vol. I.1 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1956), 183.

2. Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society, trans. John Wilkinson (New York: Knopf, 1964), 79.

3. Philip Rieff, The Triumph of the Therapeutic: Uses of Faith after Freud (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2006), 11.

4. Walter Brueggemann, The Prophetic Imagination, 2nd ed. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2001), 3–5.

5. Abraham Joshua Heschel, God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1955), 290.

6. Wade Mullen, “Impression Management Strategies Used by Leaders of Evangelical Organisations in the United States in Response to Accusations of Abuse” (PhD diss., Lancaster Bible College, 2018), 212–215.

7. James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2011), 39–40.

8. Sarah Coakley, God, Sexuality, and the Self: An Essay on the Trinity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 115–116.

9. Tricia Lott Williford, You Are Safe Now: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Resurrection (Colorado Springs: NavPress, 2023), 142.

10. Eugene H. Peterson, Eat This Book: A Conversation in the Art of Spiritual Reading (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006), 65.

11. Jacques Ellul, The Humiliation of the Word (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1985), 49–52.

12. Stanley Hauerwas, The Hauerwas Reader, ed. John Berkman and Michael Cartwright (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001), 233.

13. Karl Barth, Karl Barth and Liberation Theology, ed. Paul Dafydd Jones (London: T&T Clark, 2021), 42.

14. Wade Mullen, Something’s Not Right: Decoding the Hidden Tactics of Abuse and Freeing Yourself from Its Power (Carol Stream: Tyndale, 2020), 53.

15. Ibid., 61.

16. Tricia Lott Williford, You Are Safe Now: Finding Freedom from Fear in the Most Dangerous Places (New York: Tyndale Momentum, 2024), 102.

17. James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2011), 26.

18. Wade Mullen, Something’s Not Right: Decoding the Hidden Tactics of Abuse—and Freeing Yourself from Its Power (Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House, 2020), 88.

19. Jacques Ellul, The Humiliation of the Word (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1985), 147.

20. Karl Barth, Karl Barth and Liberation Theology, ed. Paul Dafydd Jones (London: T&T Clark, 2020), 56.

21. Abraham Joshua Heschel, God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1955), 284.